Uncategorized

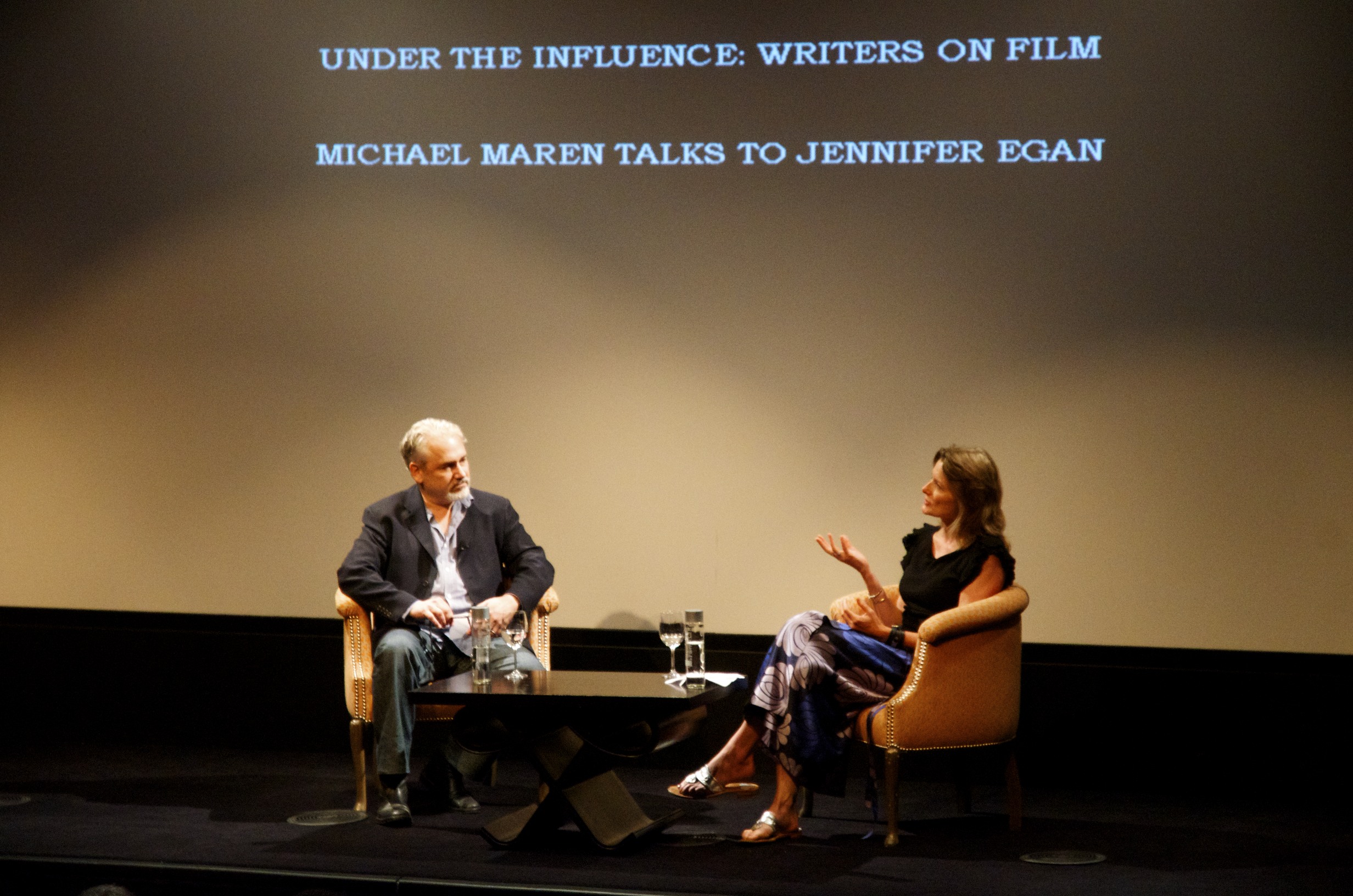

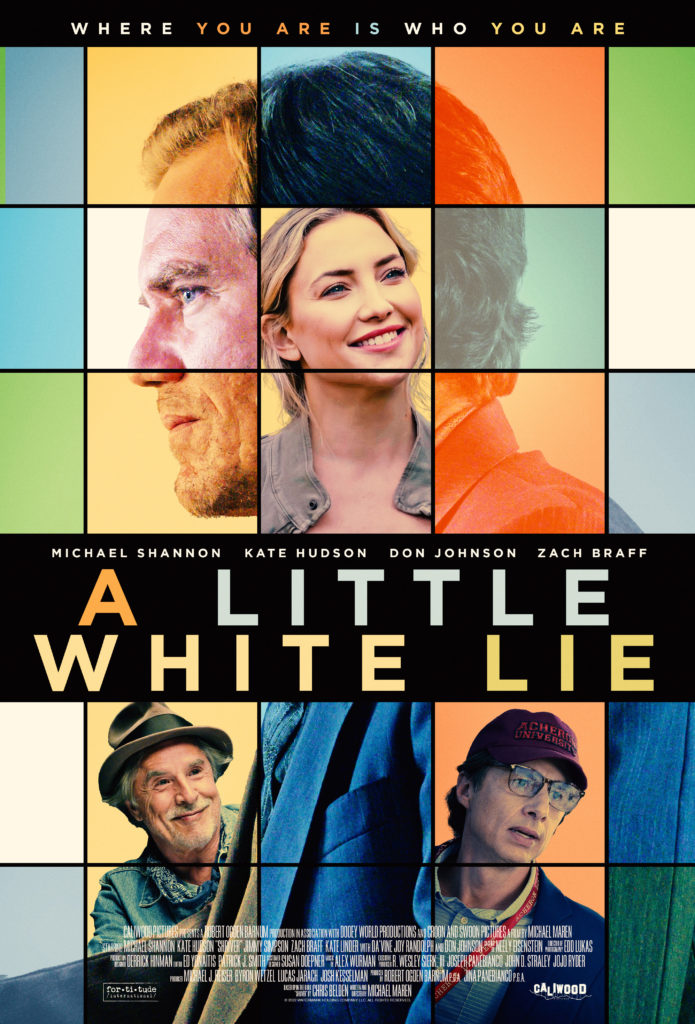

Shriver Becomes “A Little White Lie”

A filmmaker doesn't always have complete control over what a distributor calls a film.

Here comes “Shriver”

Seven years in the making, filming interrupted 400 days by COVID, "Shriver" is finally edited and moving on to the next stages of postproduction: special effects, sound, music, color. Watch this space as we create a poster, trailer, and begin to bring this out into the world.

Kate Hudson and Michael Shannon in a PEOPLE exclusive first look at Shriver | Credit: Suzanne England

Kate Hudson and Michael Shannon are teaming up for a new comedy.

In a PEOPLE exclusive first look at Shriver, sparks fly between Hudson's and Shannon's characters in the film about a New York handyman, Shriver (Shannon), who is mistaken for a famous reclusive author with whom he shares a name.

Shriver accepts an invitation to attend a university writer's festival to deliver a keynote address where he meets Hudson's Simone Cleary, an English professor. Shriver plays a dicey game as feelings bubble between the two as he continues to pretend to be the author she believes him to be.

The comedy — written and directed by Michael Maren, and based on a novel of the same name by Chris Belden — also co-stars Don Johnson, Da'Vine Joy Randolph, Jimmi Simpson, Zach Braff and Aja Naomi King. It was produced by Jina Panebianco and producing partner Robert Ogden Barnum at CaliWood Pictures.

Hudson tells PEOPLE she was drawn to the project because of the starry cast.

"I'd been a fan of Michael Shannon's work for some time," Hudson shares with PEOPLE. "I was very excited to have the opportunity to work with him. Don Johnson is a legend and an old family friend, so I was very excited to be working with him. And having worked with Zach Braff in the past, I just knew I was going to be so much fun! I'm an avid reader, and at the core of this quirky, little film about writers is the story of the simple, human connections that we all seek."

"The COVID pandemic shut down production just one week before we wrapped, so waiting well over a year to reconnect with everyone and finally finish the film made this an experience that I will always remember," she adds.

The movie was a labor of love for the cast and crew and, in particular, for writer/director Maren, who was diagnosed with cancer in 2019 after casting Shannon, 46.

After overcoming cancer, Maren met Hudson, 42, who boarded the movie. The team spent three weeks filming in 2020 until COVID-19 halted production for 400 days.

Despite the hurdles, Maren tells PEOPLE his favorite part of making the movie was "to be able to work with this incredible cast" which he says "was a dream come true."

Having to halt production due to the pandemic "felt like a crushing blow," he adds.

"But a year later the spirit with which everyone came back together to complete this film was nothing short of inspiring," he says. "Watching Mike and Kate bring their characters to life while creating some really powerful on-screen chemistry is any director's dream."

As for what resonated with him about the movie, Maren says, "I think imposter syndrome is something that most of us feel at some point in our lives. It felt like a fresh subject for dramatic and comedic exploration."

Shriver is based on the 2013 novel of the same name by Chris Belden.

Indie Go Go Go

I've been waiting to write until I have something good to say -- and I'm happy to report that I have a lot of good to say. A SHORT HISTORY OF DECAY is back in pre-production and will commence shooting in Wilmington, North Carolina on October 1. It's been quite an odyssey. We've moved the shoot to Wilmington because there's a fantastic infrastructure for film there and because it's such a friendly place for filmmaking that we're able to make the film on a significantly reduced budget. So we are a GO PICTURE. It's happening. I'm going to hold off on announcing too much right now but suffice it to say that we have continued incredible support and response from some of the best people in the business. I am amazed at the passion people have for this project, which as you all know, means so much to me.

But even though we are a GO PICTURE, we could still use some more money to put on screen. Specifically, we want to be able to send a second unit to Sarasota, Florida and to do a couple of days in Brooklyn. And so I've launched -- as of today -- an Indiegogo campaign with the express purpose of raising a bit more money, and of then giving back by taking the profits of shares that are raised in this manner and donating those profits directly to Alzheimer's Disease research.

As some of you may know, my own mother is in the early stages of Alzheimer's -- as is the character of Sandy Fisher (who I can announce here is being played by none other than the inimitable Linda Lavin). This is a project very very close to my heart. And it means a lot to me to be able to raise awareness about the disease, and in particular about the emotional complexities that the disease creates in a family. When the film is released, I intend to hold special screenings to benefit Alzheimer's, with cast members and others involved in the film taking part. I hope you'll go over to Indiegogo and see what we're up to -- and if you possibly can, please donate. Every dollar donated in this way will show up on the screen -- and will ultimately benefit not just my film but an important cause.

I will be continuing to post as I'm able to share more about the wonderful cast we're putting together. Thanks. And watch this video if you want to see me in front of the camera.

Two Steps Forward, and…

Since the purpose of this blog has been to tell the truth about all the ups and downs of the filmmaking process – and while lately all the news has been good, which is a whole lot more fun to write about – I need to tell you about the last few weeks, which have confirmed a few of the most basic filmmaking credos for me, one of which is that you don’t have a green light until the ink is dry on the check, and the check has cleared the bank.

A few weeks ago, we were in pre-production on ASHOD. The film was fully cast, and seemed to be fully funded. We opened production offices in Sarasota, Florida, and the A.D. and UPM and D.P. had all convened there. We were putting in long days and chowing down on stone crabs at Walt's Fish Market in Sarasota. We had reduced the budget of the film to the barest bones, and I had been shaving pages off the script in order to make this lean and mean shoot happen – even it if meant losing some scenes and moments that were important to me.

And then the other shoe dropped. A major investor who had committed, well… simply changed his mind. Why this happened is anyone’s guess. This investor wasn’t someone I had direct dealings with. A guy in LA was talking to a guy in New Orleans who was talking to this guy in Palm Beach. It was like an elaborate game of phone tag but with a lot of dollars attached. And then… silence. Phone calls not returned. And slowly, a pit in my stomach which grew and grew until it was confirmed.

We are going to have to postpone production. Re-group. Re-think. Find a new investor, or new series of investors. My wife turned to me (we were in a car on our way back from a funeral when this news hit us) and said “this is going to have a silver lining. You are going to look back at this, six months from now, and be glad it happened this way.”

Now, my wife is no Pollyanna. And deep down I feel the same way. We were shaving too much off the budget. Making compromises that felt nerve-wracking, all in the service of just getting the movie made on schedule. Now, my producing partner and I have increased the budget. We’re going after different investors with a different strategy. Everyone – from the cast to the crew – who has believed in this project from the beginning is still on board. All the original investors are hanging in there. They were doing this for love, and they still are. We’re going to make ASHOD, and we’re going to make it the way it needs to be made. This is the story of getting an indie film off the ground, and up until now, I am aware, I had a crazy-good run. It felt almost too good to be true. And guess what: it was. So this is the next stage of the game, and the thing that separates filmmakers who actually get their movies in the can from those who give up.

In my previous career, I was a war correspondent. This is a war – the war of art, the war of building a skyscraper from the top down, the war of combating exhaustion, disappointment and insecurity and moving forward, day by day, to the moment – we are hoping it will be this fall – when I will be saying those two, most precious words:

And…action!

The Right Direction

A year ago, when I sat down as if writing for my life, and wrote “A Short History of Decay” in six intensely creative weeks, I could not have allowed myself to dream that the project would be at this point. I’d had too many projects go up in flames, had written too many jobs-for-hire that I had to pretend to be passionate about (“Remember, you’re passionate about this project,” my manager once said to me before I went into a pitch meeting ). “A Short History of Decay” was a story close to my heart, and I didn’t dare believe, didn’t dare really do anything other than put one foot in front of the other and revise, show it to friends, get notes, revise some more, show it to more friends until finally it was ready to let it out into the world.

Well, I’m just back from a heady, borderline-surreal few days in Hollywood, with a lot to report. I flew out with my producing partner for a series of meetings with investors and actors, and honestly, it couldn’t have gone better. I don’t want to jinx the project by naming names, but for now I’ll just say that we have attached a fantastic actor who also happens to star in a wildly popular television show, to play one of the lead roles, and we have tremendous interest from other wonderful actors to play the other roles. (I'm not teasing here. I'll report the details at the appropriate time.) The big agencies are behind us. Agents are passing the script along to their clients, who are reading it quickly. I met extraordinary people who have offered help of all kinds. Doors just keep swinging open. If you know me, you know that I cannot be described as an optimist, but I will say this: we are well on our way to securing the backing that will allow us to start shooting this summer.

Many things will happen between now and then. There’s a long way to go before I’ll be able to utter the words “...and...ACTION”. But we have momentum, and I am beginning to believe that it will happen. When it does, I can tell you that it will be a story of a whole lot of years of perseverance, rejection, discouragement, and a loss of a sense of what was most important to me. It’s amazing what can happen when you remember what it means to be true to yourself.

LA Bound

Tonight I leave for Los Angeles with my producing partner for two solid days of meetings about A Short History of Decay.

As I pack for this trip, it’s with a completely different feeling than previous business trips out West. In the past, I would have spent weeks (if not months) preparing pitches in the hopes that producers or studios would pay me to develop them. I would seek their approval and await their judgment. Sometimes their judgment was instantaneous. In one case, I spent literally months working on a pitch and it was clear from the moment I walked into the room that they had taken the meeting as a courtesy, that the producer I was with had no juice with the network, and that they weren’t interested in the least bit in the subject matter. All that time, down the drain. That wasn’t a fun flight home. I can tell you the various corners in New York City where I have been standing when my agent called me to deliver the good — or more often, the bad — news. Sometimes an answer would never come; I have scripts and projects out there with producers and studios who, years later, haven’t passed on them. (Silence is sometimes the Hollywood “no”.)

The waiting. The waiting will kill you. Do you know those lists that tally up how many hours of your life you will likely have spent brushing your teeth, or shaving, or driving your kid to school? I would rather not know how many hours of my life I have spent waiting. In all the years I spent as a foreign correspondent, it went like this: write a story, file a story, see it in print the next day. One of my best stories — for which I won several awards — was actually dictated from memory over the phone from Somalia to my editor, because my computer had crashed. Which is all to say that I am not really built for the act of waiting. Nor am I built for the painful act of abandoning projects that I have worked hard on and loved, because I couldn’t get an executive or a producer to share my vision.

With ASHOD, that has all changed. No, I don’t have stars in my eyes. I’m not naive. Nothing about this process is easy. But as I meet with some amazing actors this week at the big agencies –– some of whom have already expressed interest in being in my film –– I am aware that it is entirely by following my own heart and my own vision that my small, personal film has made it to this point. I still need partners, of course. I can’t make the film alone. I still need lots and lots of help so I can forge ahead and realize my vision for this project. The difference is that it’s in my hands. Step by step, it is happening. And it feels exciting and exhilarating––and like the way it always should have been.

L.A. Incidental

I’m writing this from Tutka Bay, Alaska, about a 30-minute boat ride from Homer, which is a four-hour drive from Anchorage, which is a five hour flight from Los Angeles, where I just spent a week visiting friends and having a good time. It was the first time in more than a decade that I’d arrived in LA with nothing to sell, no meetings to take, no mad dashes from lunch in Santa Monica to a 3:00 PM in Beverly Hills where––just for instance––after I arrive, I receive a text telling me that the meeting has to be rescheduled because Mr. XYZ has been held up at a lunch meeting and evidently didn’t feel the same compunction to dash across town that I did.

No. I spent a week in LA without that crappy feeling. And without the crappy feeling that I have after mangling a pitch. Or the even crappier feeling I have after nailing a pitch and realizing that it doesn’t really matter because the project was doomed long before I walked in the door; nothing left to do but get my parking validated and go back to the hotel in time for cocktail hour.

Without all of that, LA suddenly felt like a warm and welcoming city. My wife and I hung out with some old friends and made some new ones. I had some long, leisurely lunches and relaxed dinners and didn’t spend a second fretting over traffic. When people asked my what I was up to I told them about A Short History of Decay and my plans for making the film. I received nothing but incredibly warm encouragement and support. (Much more on that later). Nobody thought I was crazy. In fact, it seemed like a lot of the people I was hanging out with were doing the same thing themselves.

I may be imagining this, but it seems that the frustration I’ve been feeling for the last few years in Hollywood is shared by most; working outside the system is becoming more the rule than the exception. The people doing this range from screenwriters to actors to directors to producers to musicians. It seems like we’re all in the same boat together, trying to forge new paths and do what’s truly meaningful to us, come what may. After all, if it’s going to be this hard, we may as well be doing what matters, right?

Crazy Rat

I’m writing this post from Cambridge Massachusetts. I spent a chunk of my youth here, my adolescent and teen years (I most definitely did NOT go to Harvard or MIT.). I loved the flavor of the place, the sense of freedom, the sight of people reading and writing in cafés, with books and papers piled around them. I always imagined that they were grinding away at dissertations about their recent discoveries in some highly specific aspect of genetics or insights into obscure 18th century poets. Later I moved to New York City, and was equally taken with the sight of people writing, at first in notebooks and later on notebooks. I imagined they were all writing novels, deeply felt tomes of startling emotional resonance.

Then, when I got into the business, I started spending a lot of time in LA. I would walk into a Leaf & Bean or a cafe in Venice and see people working away at screenplays. And I felt none of the admiration that I experienced in Cambridge or New York. My thought was something closer to: Those poor, deluded saps. Of course, I was a screenwriter myself, but I was pretty sure I wasn’t one of those saps. I felt that I was close, very close, on the verge. They were slaving away over too many lattes, and I had just come from a “big meeting" at DreamWorks.

I pulled out my MacBook Pro, booted up Screenwriter, and pitied them.

Is there anything less rewarding than being an unproduced screenwriter? The PhD candidates’ dissertations will be read by their peers and advisers. They may not in fact be groundbreaking, but they will be fully realized. They will find their intended audience and will exist as the academic works they are.

And the novels being written in New York? Most will never be finished, let alone published, but they too will exist as the “novel in a drawer” or “noble failure” or some form that bestows a measure of respect upon the author.

But screenplays? Poor saps.

Many years ago, when I was a journalist working on my second book, I went to LA to do some research. I stayed with a friend in Santa Monica, and when we were out in social situations, he introduced me like this: “This is my friend Michael from New York. He’s a real writer.” I liked it then. I cringe when I think about it now, because it’s made me wonder, am I still a real writer?

The unproduced screenplay is nothing. It won’t be read, because nobody reads screenplays for entertainment. It is unfulfilled. It is meaningless, and its author is a quixotic dreamer. Can’t get no respect.

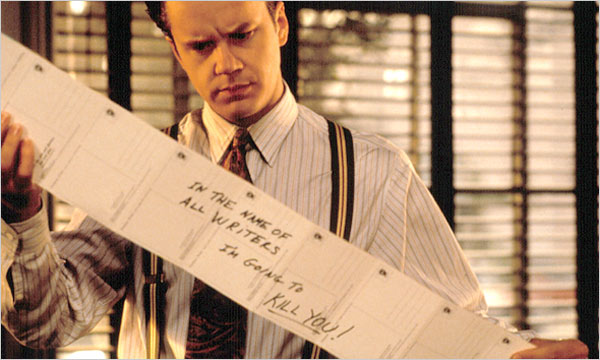

No respect because the industry does not value the effort. It values only the success and the laurels it bestows upon itself. Example: A writer wins an Oscar for a script that everyone in the biz knows he didn’t really write. He’s gotten credit because he wrote a barely serviceable first draft of a high-concept idea that was rewritten by a half a dozen other writers. Still, the guy with the award is going to be a star for a while, have projects thrown at him and even some films produced.

It’s hard for a self-respecting screenwriter to stomach. And I’ve come to dread the words “I love this script” from a studio exec. I know what’s coming next. “But...”

You get just enough encouragement to keep going. Keep plugging away at a new script. It’s called intermittent reinforcement. The animal (usually a rat) is conditioned with just enough reinforcement to keep doing the same thing over and over again. But soon that reinforcement is removed and the animal continues the same behavior with very little reward at all. It can eventually make for a crazy rat.

So, I quit--at least for now. A Short History of Decay is my attempt to get off the wheel, to stop holding on to little bits of praise and encouragement. To stop chasing the market, and believing that the occasional paycheck is enough while my soul gets slowly eroded. Like the folks writing their dissertations and novels, I’m taking control of my work and trying to make something singular and real, out of my own idiosyncratic, particular vision. Every day now, I take a few steps towards actually making this film. And for now, that’s good enough for me.

Are we on the Same Page?

Many years ago, I was writing a script for one of the major studios. In advance of a phone conference, I sent a draft of the script to the junior producer. He was my point man on the project, my supposed ally in the campaign to get the script green-lighted by his bosses and the studio. He got back to me with a number of very specific suggestions, with which I disagreed. I protested a bit, but it became clear that these were changes I needed to make if he was going to be enthusiastic as he put the script on his boss’s desk. I made the changes.

Later, in a conference call with the producers and the studio exec, the higher-ups in the room pointed to a number of things they thought needed to go from the screenplay. They were talking about the very changes that this assistant producer had insisted I make. He was in the room with the others, and I waited on my end of the phone for him to take some responsibility, or disagree. But he just piled on, adding his voice to the chorus of negativity. I could have said something at that point, but I didn’t.

Today he has the top job at an important place in the industry. I'm sure that the details of our first encounter and hundreds like it have dissolved into the far depths of his memory. I'd like to think that he recalls our time working together fondly.

I’d like to say that there are positive lessons a beginning screenwriter could learn from this story, changes in behavior or strategy that would ensure that this kind of thing doesn’t happen. But there are no lessons. There are no lessons because this is simply the way it is. Within the system there are many masters that need to be served, many disparate voices that can bombard you with bits of contradictory advice and requests and then end the meeting looking for assurance that “we’re all on the same page.”

The writer gets off the phone and is left alone in a room with the impossible task of sorting it all out, the need to please various people with differing agendas. So, like a lab rat, I learned to respond by producing not the best scripts I could, but the ones most likely to make producers and executives happy.

On a number of occasions I’ve handed a script over to an author whose book I adapted or to someone who’s portrayed in the script with this caveat: This is not the script I think should be shot. This is the script that I think will get the executives’ attention, or make the investors happy. I’ve added some scenes that shouldn’t be in there, that we can’t afford to shoot, or that simply can’t be shot. In other words, this is an extension of the pitch, not a real script. It's a waste of time and effort and, even more than that, it’s soul crushing for the writer.

Which is why writing A Short History of Decay (Can I just call it ASHOD?) was so liberating. I thought only of the film that could be made from it. There were no voices of execs in my mind. I was the only audience for the script; the standards I held it to were only my own. And then I found a producing partner who loved the script and whose primary goal is to help me realize my vision of the film that can be made from it.

The producer I’m working with is perfectly ready to move ahead with the script I’ve got. Like anyone who’s hands-on in the biz he’s considering the fact that the what’s on the page is a long way from what we’ll end up shooting, no matter how many changes I end up making. In his mind, we’re making a movie, not perfecting a document.

This puts me in a very different position than I’ve ever been in before. What I’ve been used to is producers and executives sending me back for endless rewrites on scripts that I think are pretty damn done. They do this because they’re not really sure what it is they want, and because they can, despite the fact that it’s against WGA regulations. All writers know that they’re asked to do free rewrites, yet those who complain about it are labeled troublemakers and will have a harder time finding work next time out.

I’m doing a rewrite anyway because I’m not entirely satisfied with all of my characters. I’m doing a rewrite so I can better define some of those characters for myself. I need to be careful, as I’m the king of the kind of painstaking, time-sucking script fiddling that rapidly reaches a point of diminishing return. As I alluded to in the previous post, I spent a month — almost as much time as it took me to write the entire script — making the small changes suggested to me by some readers. Like Penelope, taking apart the tapestry she spent the day weaving, I endlessly wrote, unwrote and rewrote scenes and dialogue until… until nothing. There’s no end to that, and I needed to once and for all get the thing off my desk before I grew to hate it.

So I’m determined to hand the script with production breakdowns over to the producer this week so he can get to work on a budget and pass it along to a casting director. I have a rough idea of what the budget should be, and some very specific ideas about which actors I want to approach. Those two variables are of course inextricably linked. But this is material for many future posts.

See the first post in this series.

See the next post in this series.

A Short History of Decay

On Friday morning, I met in New York City with a legendary producer of many independent films that I admire, films that have risen above the crowd to critical success and Academy Award recognition. He’s a hands-on producer who often doubles as first assistant director, something that I as a first-time director absolutely need to have. He can do a budget for the film, hire a crew almost anywhere I need to shoot. He’s got access to everything I need from casting director to key grip. And, very important, his name on the project would signal the talent and investors I need, that this is a serious undertaking with an experienced hand at the helm.

I had no idea how the meeting would go. My fear and my expectation was that it end with him offering only mild encouragement: “I enjoyed reading your script. It’s not really what I’m looking for right now. Best of luck with it.”

But, let me back up. Meetings at this level don’t just happen. If you stick your script in an envelope and mail it off to a major producer it will likely be tagged, sealed and filed, unopened and unread. The reason is that if ten years from now the producer makes a film about a zombie roller derby, and your script was about zombie ice hockey, he or she will need to be protected from your suspicion that your brilliant idea has been stolen. In other words, you need an in.

Let me back up again. I had a friend in graduate school who I used to hear from pretty regularly for years after we’d last seen each other. We went in different directions, and had very little in common, but a few times a year the phone would ring and there he was, though we had less and less to talk about. When I finally asked him about his regular calls he told me that he made a point of cycling through his Rolodex (yes, it was a long time ago) and staying in touch with three or four people a day. “You never know when you’re going to need someone’s help,” he admitted.

I wasn’t quite appalled by this, just puzzled. I had to admire his foresightedness, but I also knew that I could never do something like that. It’s not in my character to network and to spend time talking to people I don’t genuinely enjoy talking to. (Years later, when I was an editor at New York Magazine, he got in touch and sent me a a copy of a book he’d written. I told him that I couldn’t help him because it wasn’t right for New York. I never heard from him again.)

All I’m saying here, is that while I’ve made some friends in the film business, I’ve never stayed in touch with or even kept a list of contacts who might be able to help me out in the future. I have, on the other hand, made some real friends. And I knew that I’d need to ask them for favors to start to move this project forward.

And the first favor I needed was for some of them to read my script. And that’s a huge favor. You’re asking someone, a busy someone, for two hours of focused attention when they could be doing any number of other things. People ask me to read their scripts all the time. And I do it only for good friends and as a favor for friends of good friends. I’ve learned over the years that what most people are looking for is affirmation of their talent and are hoping that I’ll be able to pass the script along to someone I know who can move them to the next level. (Though I do sometimes feel the way this guy does.) So when I ask people to read a scripts of mine, I insist that they read them with a brutally critical eye. After I’ve spent however many months in my cave writing a script I honestly have no idea if it’s any good at all. I need a massive dose of reality.

The first person I gave the script to was an actor friend. He’s an amazing actor and one of the smartest people I know. He’s done a ton of theater and has had tour de force roles in any number of feature films. I wanted an actor’s read, because if this project was going to have any chance at all to succeed I need to have written roles that actors would want to play, and play for a lot less money than they would normally get.

We met for lunch several days after I’d handed him the script. He came with notes, some really insightful critiques of the characters as well as some plot points that he thought I’d left undeveloped. It was an encouraging meeting, but also one that sent me back to my cave for a month. (It shouldn’t have taken me a month to do those revisions, but that’s a story for another time.)

I’m not going to pretend that there’s no luck involved. Because if I were living in St. Louis or even in LA, this might not have happened. But I live in the northwestern corner of Connecticut, a beautiful rural place that is also the weekend or permanent home to a lot of people in the arts.

So I asked a good friend, an academy award winning director, if he would read my script. I did this with a pit in my stomach, even though he never hesitated. He had read some of my scripts before, but only after he’d asked me for them. But that was just one friend curious about another’s work. This time I handed him a script looking for help. Looking for affirmation that I wasn’t totally deluded about what was written on those 118 pages.

It was this director who passed it on to the producer in New York. And there’s no way in hell that the producer would have even read the script if it hadn’t come from this director. (He’s in preproduction on a film in New York at the moment.)

So when I walked into the production office on Friday, I had reason to fear that our meeting was a courtesy to the director who had handed him the script in the first place. After some small talk — anecdotes exchanged about our mutual friend — he started talking to me about the script. It slowly dawned on me that he was talking about it in the manner of someone who had thought about what we would need to shoot it, where he could find the crews and how many shooting days we’d need in various places.

And after talking to him for a while, I needed to hear him say it, so I asked him directly: So are you going to work with me on this movie? And he said, yes. Yes, we’re going to move forward and try to make this movie. It’s been a while since I’ve heard a “yes.” And I know that this “yes” by no means gets this film made. There still lies heartbreak and tribulation ahead. But it’s a step. An important step that makes this all the more real. I wanted to hug him, but I didn’t.

P.S. He preferred my original title, so it's back to A Short History of Decay. For now.

See the Next Post in this series.

In Search of the Elixir

Yesterday I went to Film Forum in New York City to see Meek's Cutoff, a film that was highly recommended by a friend. It's directed by Kelly Reichardt, who also directed Wendy and Lucy. The film, set on the Oregon Trail in 1845, is both highly realistic and dreamlike. It beautifully captures powerful emotions, reveals the inner lives of characters who aren't exactly articulate. (It seems that modern films that deal with subtle emotional stories tend to be populated by writers, psychiatrists or academics who traffic in self-reflection as a matter of course.) For my money, this film blows True Grit out of the water. If you're going to see only one film about the old West this year....

Anyway, that's not what I was blogging towards. As an added bonus, Michelle Williams, who gives a beautifully subtle performance in the film, arrived to do a brief Q&A with the audience after the final credits. The folks who raised their hands all seemed to be "in the biz," or aspired to be in the biz. And the questions all flowed around the same theme: What do you know that can help me?

They were the kinds of questions that no one can answer: "What would you do if you were me?" Correct answer: "How the fuck should I know? I'm not you." There followed more questions about how the film got made that were really asking, "Tell me how I can do this." If I hadn't been sitting in the second row I would have walked out at that point

"You've made some great choices to get to where you are today vis a vis the indie film world. How did you make those choices?" To her credit, Michelle tried gamely to politely address the desperate anxieties of the questioners. But the questions kept coming, as if her success is the result of some secret she's learned, as if there's some elixir out there that turns ordinary folks into successful producers, actors or screenwriters. At one point, an audience member turned to a particularly persistent questioner and told her to shut up. She didn't. Finally Michelle Williams said this: "Be yourself. Lead an interesting life. Don't take anyone's advice." (I'm quoting from memory here, but it's close enough.) It was the perfect answer for an audience of questioners who were in fact trying to be someone else; trying to be Michelle Williams or Kelly Reichardt or anyone but themselves. And while there's no road to success, that's a surefire recipe for failure.

Chasing the Market in Hollywood

Several years ago I was pitching a film to a producer who had a deal with one of the major studios. My story hewed closely to a real life tale about some super smart middle class New York City kids who turned themselves into expert gamblers. They started playing online and eventually ending up in turning cards at underground casinos run by Russian mobsters in the netherworld of Queens. Their story arc took them from smart kids planning on attending elite universities, to wise-ass, know-it-all winners with delusions of grandeur. Of course, the bubble bursts and by the third act they’re in debt to the mobsters and frightened for their lives. The main character, who had already been accepted at Stanford, finds himself being trailed and beaten up by a gang of prostitutes who work for the mobster. And, eventually, one of the kids is killed fleeing a casino. That’s the low point, and a measure of redemption follows. It’s a good story.

The producer stopped me in the middle of the pitch. “That’s not what’s selling right now,” he said. “We’re looking for political stories. People are focused on the war in Iraq. That's the kind of stuff we want. Can you write that?”

This was 2006, a slate of films based on events in Iraq and Afghanistan were lined up for release. Rendition. Lions for Lambs. In the Valley of Elah. That’s what they were looking for.

Shit, I thought. That was the stuff I wanted to write. I’ve been in war zones in Somalia, Ethiopia, Sudan... I can spin those tales in my sleep. That, I figured, was my sweet spot. But I didn’t pitch anything like that because I was thinking, “Who the hell wants to see a film about Iraq when it’s on the news and in the papers every day?” But I went back to the drawing board and tried to come up with a war movie.

I should have stuck with my instincts. All of those films bombed. A few months after my meeting you couldn’t get anyone anywhere to even hear a pitch about a war movie.

The film that did really well that year: 21, about a bunch of MIT kids who make a fortune in Vegas and then.... you know what happens. My story was better, grittier, truer.

I should have learned my lesson then. When my agent told me that political thrillers were selling, I went and wrote one. It was awful. That’s not how my brain works. I’m never going to be able to write a tightly-plotted caper film.

The lesson is to stick to your guns, and do what you do best. Someone — an exec, an agent, your actor buddy — is going to tell you quite correctly that what you want to do isn't what's selling right now. But unless you can spit out a screenplay in two days, the market is always going to be squirming out of your grasp.

I just finished a spec; a quiet family drama. A dark comedy. I've been told that those things aren't selling right now — which is fine with me, because I'm not going to sell it. I'm not going to chase the market. I'm going to make it. Stay tuned.

What’s the Best Training for a Screenwriter?

What do these screenwriters have in common? Joe Eszterhas (Basic Instinct) Paul Attanasio (Quiz Show) Cameron Crowe (Jerry Maguire), David Simon (The Wire), Mitch Glazer (Great Expectations), Nora Ephron (When Harry Met Sally), Nicholas Pileggi (Goodfellas) William Monahan (The Departed), Mark Boal (The Hurt Locker) and, well, me.

They all started out as journalists. And there's no better training for a young screenwriter. Here's why:

1. It's real-world experience like you'll never never find in any other profession. Too many young screenwriters know lots about movies but little else. That's why many scenes in movies you see are constructed of tropes from other movies; they ring false in terms of real life. Whether you're covering the war in Afghanistan or your local school committee election, journalism puts you up close with real people in real situations at times of stress when big things are at stake. Most young writers have never experienced a situation like first hand.

2. What's the story? That's the question that both a journalist and a screenwriter need to ask constantly. Stories, whether on the screen or in the local paper, have beginnings, middles and ends. They have cause and effect, shape and form. Real life, contains none of these things; it's messy, disorganized, and never really reaches a conclusion. Beginnings, middles and ends are structures that we impose on our lives to turn them into stories. It's the structure that journalists impose on news stories to make them readable and understandable. (Which, by necessity, oversimplifies things and implies cause and effect where there is often none.)

Both a journalist and a screenwriter begin the creative process by combing through chaos until it starts to take a shape. It's a talent, but it's also a skill that all successful journalists develop.

3. Listening. Any good journalist develops an ear for dialogue. A good journalist knows how to listen and notices the cadences and telling details contained in characters' speech. A journalist comes to understand the layers of subtext behind what people say.

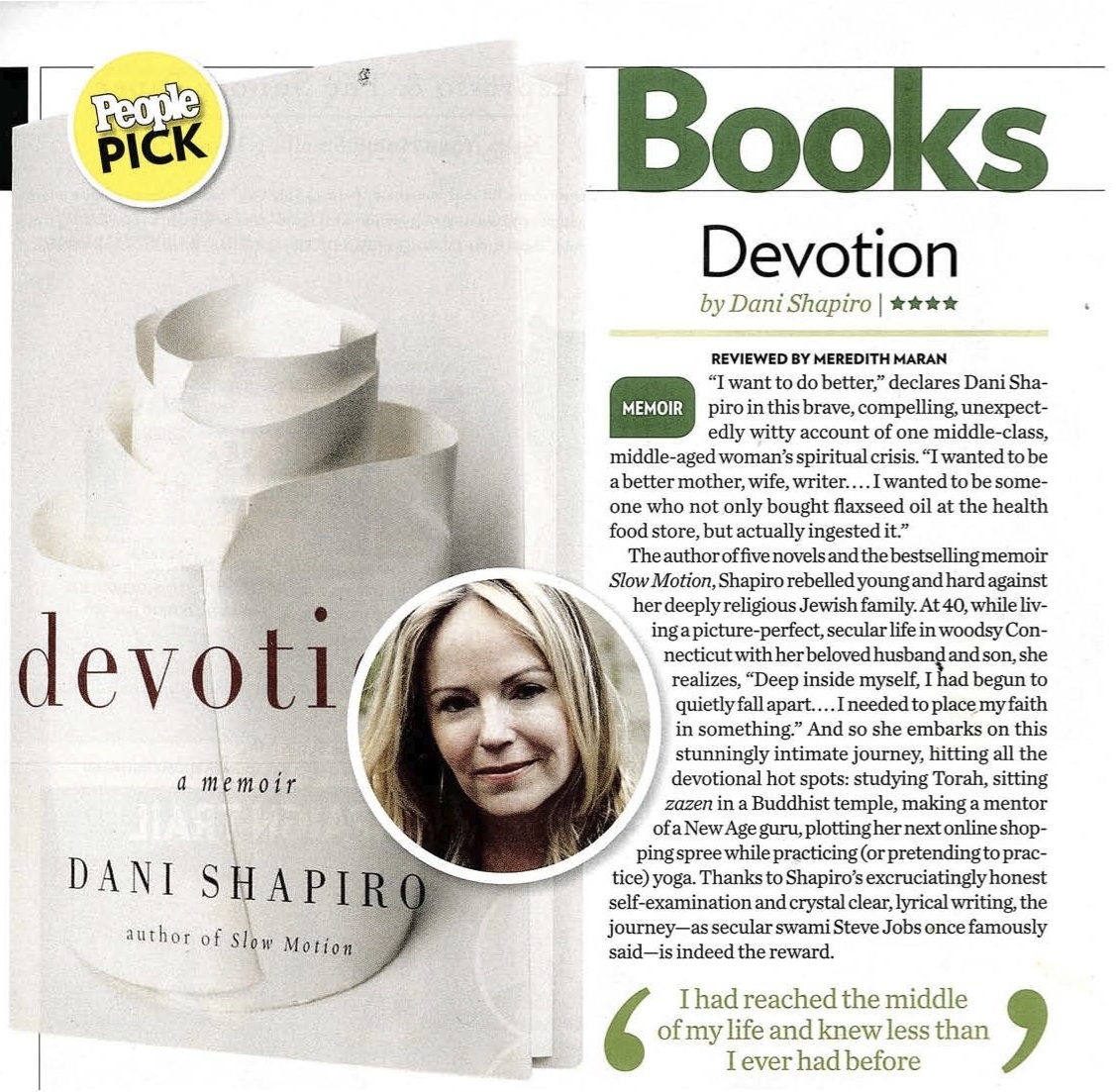

4. Details. In an interview last year, Mark Boal said, "Journalism is all about telling a story through detail, so I took that aspect with me to screenwriting." Screenwriting is also very much about detail. In my interview with Paul Auster for Writers on Film earlier this year, Auster said that in films, objects stand in for emotions. It's mostly a question of which objects/details to focus on. Both the journalist and the screenwriter are constantly involved in the act of sifting through reality to find exactly the right details.

5. And lastly, economy. Unlike novels, articles and films are brief and self-contained. There's no room for lengthy digression and contemplation. Each moment and word is loaded with all that it can bear. Each one is precious, and if something doesn't belong it has to be mercilessly cut out.

I'm aware that both journalism and screenwriting are professions in flux right now. It's harder to make a living in both professions than it was a decade ago. So in that way as well, I suppose, fighting to be heard and read in the world of journalism will get you ready for the trenches of Hollywood.

Save the world from naive do-gooders

By Simon Jenkins

Many years ago I was invited to dinner with the actress

Shirley MacLaine. I was a serious fan. I watched

mesmerised as she held the company in thrall, eyes

flashing, red hair bobbing. She was talking not of her latest

show but of her recent visit to China, then reeling in the

aftermath of Mao's Cultural Revolution. Slowly my

wonder turned to horror. The great star had been taken

for the mother of all rides. She said that Mao was a hero

of all time. He had fed and clothed his people and led

them into the promised land. No, no, she cried against all

protest, we should go and see for ourselves.

Mao's corpse count was then surpassing those of wartime

Germany and Russia, but Peking offered a well-oiled

welcome for sympathetic celebrities. The effect was

impressive. The killings and famines went unreported and

Mao became a cult in the West. Nor was Mao the first at

this game. The same was true, in their day, of Stalin,

Mussolini and Hitler, and more recently of Nkrumah,

Amin, Castro, Mengistu and Pinochet. Through the fog of

distance shines the glamour of power. The eye reports

what it sees, not what it fails to see - or is not shown.

All political globetrotters should watch Daniel Wolf's

BBC2 documentaries, Tou rists of The Revolution,

being aired at the ludicrous time of 5.50pm on Saturdays.

It is no travelogue. It is a testament that travel narrows as

well as broadens the mind. We are shown Britons exulting

at Mussolini's charisma. We see Lloyd George describing

Hitler as "the greatest German of his age". We hear an English

journalist telling Hitler: "England's youth loves you, Führer".

George Bernard Shaw visited Russia in 1931 and

witnessed "an atmosphere of hope and security as has

never before been seen in a civilised country on earth".

The veteran Marxist, Christopher Hill, still refuses to

believe in Stalin's deliberate Ukrainian famine. Barbara

Castle, then a journalist, reported "no atmosphere of

repression" in prewar Moscow, only glorious

opportunities for women. After the fall of Stalin, the

Writers Union lavishly entertained British celebrities. I

wonder if the young Melvyn Bragg was aware that he had

been "framed" by the KGB for star treatment on his visit.

These "tourists of the revolution" may have given only

scant satisfaction to the regimes that hosted them. Some,

such as Nigel Nicolson, are now gracious in contrition.

Like others who admired German fascism, he recalls the

impact that a disciplined nation with a clear sense of

mission made on a radical young mind, when Britain

seemed reactionary and lost in depression. Michael Burn

was so ashamed of saluting Hitler that he subsequently

fought in the Second World War, was imprisoned in

Colditz and became a communist.

Tyrants have always evoked idolatry, especially in those

far from home. Less explicable are the cheerleaders for

post-colonial Africa, depicted in tomorrow's programme.

For them the habits of empire died hard and the inclination

to meddle was irresistible. The role of white advisers in

bringing socialist planning to sub-Saharan Africa has long

been ridiculed. Wolf's description of these adventurers as

"tourists of the revolution" seems apt. Reg Green, aide to

Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, appears single-handedly to

have wrecked an entire economy. No disaster inflicted on

Africa by imperialism seems to have been worse than that

inflicted by its successor ideologies, socialism and

"overseas aid". Ghana's Volta River project made the

colonial groundnuts fiasco seem a mere peccadillo.

The definitive Western intervention was in the Ethiopian

civil war of the mid-Eighties. Whether Bob Geldof and the

aid agencies saw themselves as tourists may be moot. In

retrospect their good intentions seem awesomely

misplaced. We see Geldof screaming on television, "Send

the money, just send the money". A billion dollars of aid

was duly sent, 90 per cent of it to prop up the disgusting

regime of the dictator, Mengistu. The World Bank and

United Nations lavished money on him. They paid for the

depopulation (now termed ethnic cleansing) of highland

areas. Food aid and vehicles followed his troops but were

denied to rebels, who had to wait until 1991 to topple the

United Nation's protégé. The UN chief in Addis Ababa

remarked on Mengistu's "intelligence, dignity and

courtesy" and asserted that the forced resettlements were

"voluntary". This was not 1885, but 1985.

Desperate not to stanch the flow of Western cash, aid

agencies colluded never to mention the civil war.

Throughout the Ethiopian crisis, the impression conveyed

to the West was that the country was suffering a natural

disaster, a famine, not the deliberate suppression of

rebellion by starvation. When the French agency,

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), could stomach it no

more and protested to the regime, it was duly expelled. Its

boss at the time, Rony Brauman, remarked that colluding

with Mengistu meant "saving a thousand lives to condemn

a hundred thousand". The fight between Brauman and

Michael Priestley, the UN chief in Ethiopia under

Mengistu, was a classic of the new imperialism. Priestley

accused MSF of "grandstanding to get publicity". The

charity accused him of being a "Mengistu pawn" and an

"accomplice of massive oppression". The spectacle of

Westerners playing professional games with a war-torn

African country is not edifying. Those who felt obliged to

eulogise Mengistu were in a line of descent from those

who admired Mussolini for "at least making the trains run

on time". They claim that they did more good than harm. I

would say, they badly need to prove it.

One sceptic of Western intervention in Africa, Alex de

Waal, asks: "How could so much good intention go so

tragically wrong?" The answer must be the same as drove

Dickens to create Mrs Jellaby in Bleak House: his

outrage that his London friends would give readily to

overseas causes but not to domestic ones. Starving

Londoners were regarded as "naughty". Starving Africans

were noble, and far less likely to land on your doorstep.

The thousands of aid workers, volunteers and journalists

who poured into Africa's periodic trouble spots

undoubtedly saw themselves as well-intentioned. They still

do today, as does the soldier in a UN beret. But then so

did the visitors to Stalin's Russia and Mao's China, and

the advisers who tried to socialise Africa's economies.

Just as aid is never impartial, so any traveller to a problem

land carries political baggage. He soon becomes a missionary,

in search not of evidence but allegiance. As Hannah Arendt

said: "The Third World is not a reality, it is an ideology."

The instinct to charity is natural. But these films make me

aware how horribly close is the path of charity to the

abyss of hypocrisy. Dickens was right. Abroad is so much

simpler and more glamorous than at home. The British find

it hard to secure peace in Northern Ireland or build a

hospital system that works. They hate being lectured by

outsiders. But they claim to know, beyond all

contradiction, precisely what is going wrong in Iraq and

Serbia and Chechnya and Indonesia. If the resulting

intervention screws up, if bombs land awry or dams go

bankrupt or dictators refuse to be toppled, nobody really

cares. Foreign crises are to hand when we need them, and

far away when we do not. Like servants, they know their

place. The imperialism of the mind is no more attractive

than that of the sword or the dollar. We can witness, but

not live, the lives of others. I find it ironic that the West

has become ever more disciplined towards the world's

natural environment, fighting to preserve its autonomy and

diversity. Yet we relentlessly abuse its political ecology.

We refuse to believe that we might not know what is best

for distant polities and peoples. This week British troops

are still dropping bombs on Iraq, believe it or not, and

overseeing the forced removal of Serbs from Kosovo.

Most Britons have probably forgotten the reason.

Meddling feels good.

The last word lies with that most sensitive student of

Africa, Basil Davidson. Surveying the deeds of Europeans

in that continent over the past century, he flatly denies that

they have known what is best for Africans. Please believe

me, he cries, "Dear friends, you don't know best, only worst."

So caveat viator. The tourist should stick to his sunbed,

and Shirley should stick to her song.

Letter from a Young Aid Worker

I received this email last month from a Peace Corps Volunteer recently returned from Senegal:

Michael,

Thank you for sending along your email address. I read your Might interview a few months ago and shortly afterward picked up The Road to Hell.

I left for PC Senegal in Sept. of 2008 and lasted about a year before coming home. The sentiments from your Might interview and your book struck me because I share so many of them. I've often reflected on my PC experience since returning from Senegal, and I've tried to write about it at various points with varying degrees of success. So it was heartening to read your words and relate to them so much.

I'm convinced that most foreign aid, whether 'official development assistance' from rich govts to poor ones or NGOs planted in Haiti, does more harm than good. Personal experience and a background in economics and an independent study of aid (I guess you could put me squarely in the Bill Easterly camp) have led me to this conclusion. It seems to me that most aid is given to meet donors' needs, doesn't have proper local context or long-term incentives to be successful, and helps us sleep well at night on our clear consciences back home in the West.

I have ranted about these issues on random blog posts and even in an op-ed I wrote last year about Haiti. But I also recognize that the demand for aid is probably not getting any smaller any time soon -- governments have all sorts of political and diplomatic reasons for giving it, corporations have to get rich off of the aid racket, and individuals will always feel the need to "do something" or "take action" for those poor souls in "Africa."

I'm currently working as a research assistant at a think-tank in DC, working mostly on tech policy. I am passionate about aid, however, and sometimes find myself ranting at friends/sisters who are wearing TOMS shoes.

Do you think it's worth it to try to change minds on the aid issue? I've often thought about ways to try to do so, which range from looking to work for an organization that fights to reduce aid / limit bad aid (if any actually exist) to traveling back to sub-Saharan Africa and interviewing locals about their thoughts on aid and writing / podcasting / filming them.

But at other times, I think I should just say Fuck It and get on with my life -- after all, who can ever convince people that aid is harmful when the other side can just show a 30 second clip of starving kids with a Bono voice-over telling them to give money to X organization or children will die?

I'm curious to get your thoughts on this, because I can't tell whether you wrote about aid for a while and then turned wholly to writing screenplays and running writing conferences or you're still interested in aid stuff. I think Easterly et al. do great work revealing many of the harms of aid, but I also think that much of that work is confined either to academia or the blogosphere.

I wish there were effective ways at least to swing the mainstream pendulum slightly toward a more skeptical view of aid, and I'm curious to get your thoughts on these issues.

Please excuse the length of this email, and many thanks for reading.

My best,

Tate Watkins

Tate,

This may be a subject better suited to a phone call than an email exchange. My short answer to your question is that it's definitely worth trying to change minds. Minds to get changed; policies take longer. When I published my book my editor wanted me to be more optimistic. He wanted me to provide solutions, i.e. more things that WE can do. But I don't think WE can do anything. We'd be better off focusing on things we should stop doing, such as sucking up half the world's resources and subsidizing our own production of crops that are more efficiently produced in the developing world. But that's a harder sell. People would rather send 20 bucks to an NGO and get on with their lives.

I'm still doing this "work." I was on the BBC last week talking about Haiti and the 3000 NGOs that have invaded that country. But, no, I'm not doing research or traveling in Africa these days. I did that for nearly 20 years, and now I'm married with a young kid and I'm enjoying that part of my life. But life is longish...relatively. You can do both. Spend some years trying to change minds, talk to the people with the TOMS shoes or the Save the Children ties, and self-rightous attitudes.

I do think that I succeeded in changing a number of minds over the years. Certainly a generation of aid workers has read my book. When the issue of the negative impact of aid is raised there are a large number of people who yawn and say, yeah we know that. That only seems like old news because of the work of myself, David Reiff, Philip Gourevitch and others. (Did you see Gourevitch's article in the New Yorker in October or so? )

There really is no organization that does this work. There should be. Bill Easterly is the closest thing to a professional naysayer we've got. I suppose that having a university affiliation is necessary to really follow this calling. That's never interested me, so I get to write movies and run literary events, both of which are passions of mine.

You have inspired me to pick up this ball again. I've been meaning to get my blog back up and running, and I'll do just that.

If you don't mind, I'll publish your letter to me and this response on the blog, It might start an interesting discussion.

Very best,

Michael

Fifty Years of Peace Corps

I joined the Peace Corps right out of college in 1977. There was never any question about that for me, and it seemed that the idea of the Peace Corps had always been with me. I think that the first actual volunteer I ever spoke with was Paul Tsongas, the late senator (and congressman at the time) from Massachusetts who I worked for on Capitol Hill. Paul had been a volunteer in Ethiopia in the early days of the Peace Corps, and often (to me, at least) referred to his experiences there.

It's been a time to reassess the Corps. This article in The Nation (which mentions me) is very thoughtful.

The only person on the dais who expressed any uncertainty about the value of the Peace Corps was Mary Jo Bane, the Kennedy School academic dean and an early volunteer in Liberia. She commented that the Peace Corps probably helped President William Tubman maintain power longer than he would have otherwise (as Tubman grew increasingly dictatorial before his death in 1971, the efforts of volunteer teachers and rural advisers arguably helped him create an appearance of government concern for the poor), which she said "might or might not have been a good thing."

Hello world!

Welcome to WordPress. This is your first post. Edit or delete it, then start blogging!

Is “Fair Trade” Just Another Marketing Tool?

Back when I was a Peace Corps volunteer in Kenya, I used to watch the local farmers cart their freshly picked coffee beans off to the local coffee co-op. There, they exchanged the beans, and six months of hard labor (or more likely, the labor of their wives) for...well, for very little. Because most of them were in debt to the coffee co-op for school fees, fertilizers, hardware, and other necessities even before they brought the beans there. And then, using a formula that was indecipherable to the farmers, the people who ran the co-op calculated a payment. Which the men promptly spent on beer. But that's another story.

Back when I was a Peace Corps volunteer in Kenya, I used to watch the local farmers cart their freshly picked coffee beans off to the local coffee co-op. There, they exchanged the beans, and six months of hard labor (or more likely, the labor of their wives) for...well, for very little. Because most of them were in debt to the coffee co-op for school fees, fertilizers, hardware, and other necessities even before they brought the beans there. And then, using a formula that was indecipherable to the farmers, the people who ran the co-op calculated a payment. Which the men promptly spent on beer. But that's another story.

The story here is that the farmers had no choice where to sell their coffee. The so-called coffee co-op dictated the price and that was the end of it. In other words, this was NOT fair trade. The farmers were in effect indentured servants to the co-ops, which were controlled by powerful politicians on the local and national level.

That's why I was so optimistic about the Fair Trade movement. Like a good citizen of the world I only buy Fair Trade coffee. (Mostly from CoffeeFool) Skeptic, that I am, however, I always suspected that much of my coffee probably wasn't really fair trade. The task of certifying what is fair trade and what isn't strikes me as impossible to monitor in the conditions where most of the world's coffee is grown.

And of course there are other complications, and this excellent article by Jill Richardson in Alternet, does a nice job of laying them out.

Despite the certification program and the often intimate relationship between growers in the Global South and roasters in the Global North, it's not easy to quantify how the Fair Trade price translates into improved quality of life. Coffee comes from countries on several continents, each with its own currency and economy. Thus, a living wage in Ethiopia may not be a living wage in Peru, or vice versa.

Ultimately she concludes:

For a consumer, the choice is clear: buying Fair Trade is the way to go. However, consumers should be aware of the nuances within the Fair Trade market in order to make the most ethical choice (and hopefully enjoy some delicious coffee, too). First of all, make sure the coffee you buy is actually Fair Trade-certified, as corporations looking to undercut the Fair Trade movement will sometimes market their coffee with various ethical-sounding certifications. (For example, Sara Lee, one of the world's four major coffee buyers, markets some of its coffee as UTZ certified -- a certification with relatively weak standards.)

I agree. If nothing else, the Fair Trade movement makes plants the idea in the Western consciousness that much of what we enjoy from the comforts of our homes is the result back-breaking labor by people caught in intolerable poverty. I have not doubt that the Fair Trade movement has improved thousands of lives across the globe. And, it's a pretty good marketing tool as well. Fair Trade requirements need to be strengthened and standardized. And ultimately, much of the money spent on foreign "aid" programs would be better directed to enforcing that certification.

In Darfur, the Relief Effort Kills

A largely overlooked article in yesterday's New York Times points to a study that shows that 80 percent of the deaths surrounding the the crisis in Darfur came not from the conflict and the actions of the janjaweed but from the very fact that refugees were gathered in huge unsanitary camps. They died from disease, not violence. They died from malaria, pneumonia, diarrhea. This is what happenens when when people who are accustomed to living in remote environments in small groups are pressed together in city-sized refugee camps.

What the Times article does not address is the reason the refugee camps exist in the first place. They are not natural gatherings of the victims of violence; rather they are people who clustered together at at points where relief agencies have put food and supplies. Ultimately. when the NGOs talk about the horrors of Darfur, they are talking about horrors they helped enable. Refugee camps, are set up for the convenience of the relief effort, and clearly not for the benefit of the refugees.

I saw this and wrote about it in Kenya in the 1970s, Somalia in the 1980s. In Cambodia, Ethiopa, Goma (Zaire) the pattern was repeated. People who gathered and died in Refugee camps might have stood a better chance if they'd stayed put. 80 percent!

Clearly a new model of refugee relief is needed, one that spreads refugees over a greater area. This is, of course, makes things much more complicated and difficult for NGOs. And it wouldn't set well with host countries, who prefer to keep the "guests" from outside in what could accurately described as concentration camps. But this is clearly a case of, if the NGOs can't do this right, everyone would be better off if they didn't do it at all.

The Role of Aid in the Enslavement of Haiti

I'm not an expert on Haiti. I've never been there, and I don't believe that my expertise in Africa qualifies me to make statements about the destructive role that "aid" has played in the epic tragedy that is the history of Haiti. So I'll let others, who know better, make the argument for me. This is from the report that I heard this morning on NPR.

Haiti has been damaged by decades of misrule ... but, most of all, I think Haiti has been damaged by development policies and programs over the past 40 years that have not taken into account the aspirations of Haiti's people," [Robert] Maguire said.

One reason was that development policies in the 1990s focused on building up factories and the "Taiwanization" of Haiti, Maguire said, without considering factors that made Taiwan successful, such as investments in agriculture and universal education.

To Help Haiti, End Foreign Aid

From the Wall Street Journal:

A better approach recognizes the real humanity of Haitians by treating them—once the immediate and essential tasks of rescue are over—as people capable of making responsible choices.

How not to help in Haiti

A friend came to me yesterday and told me that her son-in-law was about to get on a plane to Haiti to help out earthquake victims. She wanted to know what I thought about that. (Truth be told, she wanted ammunition to help talk him out of it.) I asked her if her son-in-law, who I know is an actor, had any experience in disaster relief. He didn't.

It brought to mind an experience I had in Somalia many years ago. We were in the middle of a humanitarian crisis caused by the civil war in the Ogaden region of Ethiopia. One of the NGOs, (Save the Children, I think) sent over a dozen college students to help out. I remember that the NGO staff on the ground were furious. The volunteers showed up and had to be trained, fed, housed and generally kept out of harms way. It drained valuable resources from the ongoing relief effort and accomplished very little in the end.

My advice to my friend was to tell her son-in-law to wait six months. The country will still be in devastating condition. It will be out of the news. Donations will have slowed to a trickle, and volunteers will be harder to come by. She passed the information along, and he took my advice.

From an Expert: Haiti Donation Advice

I contributed this to the Travel + Leisure Blog, Carry-On

Aid and relief agencies are rushing to assist the people of Haiti after yesterday's devastating earthquake. But they can't do it without you or, more accurately, without your money. Although it's really easy to donate your dollars, it is unimaginably difficult to actually help people. The best fund raisers in the business are not the best relief workers in the business.

If I learned one thing during nearly 18 years as an aid worker and journalist in Africa it is this: Nothing is simple. Helping people is much more complicated than just delivering food and medical supplies. To accomplish these tasks with even moderate success requires tact, skills, knowledge, and political savvy that can't be learned from books and newspapers.

So take a minute. And take some responsibility. As a donor, you are responsible for what is done with your money. And the wide range of organizations who need your money aren't going to do the same things with it. And how do you know what your favorite charity is planning to do in Haiti? Ask them. Demand that they put the information on their websites and in their PR material. It's not enough that they slap pictures of suffering Haitians online.

What do you need to know? First and foremost, is your favorite charity already working in Haiti? Have they had personnel there for years, with contacts in affected areas? Do the really know the country and the local leaders who will help deliver aid quickly and equitably to those who need it most?

If an organization isn't already set up and ready to go in Haiti, your donations are going to go to help them build an infrastructure, set up offices, and hire staff. It makes more sense to donate to an organization that already has these elements in place. This might seem obvious, but in the aftermath of the destruction caused by the tsunami of 2004, organizations who had never worked on the ground in affected areas raised hundreds of millions of dollars, much of which never reached its intended recipients and succeeded only in bolstering the stature of the organizations.

I realized that some of this is vague, and I've yet to mention a single organization, but that is deliberate for two reasons. First, in a world prone to disasters and famine, we all need to be skeptical consumers. We need to put at least as much time into choosing a a relief agency as we do into choosing a breakfast cereal. And second, the organization best able to deliver aid to Haiti is not necessarily the one that would be best to respond to a famine in Zimbabwe. Each situation carries with it unique challenges, and we need to support the group best able to cope. It stands to reason that no single organization is the best in every place and circumstance.

So where did I send my money in the case? Oxfam America. But you should do your own homework.

Want to help? Then make life harder for the aid agencies

Tim Hartford, author of ‘Dear Undercover Economist’ contributed this to the Financial Times.

A club sandwich, a pair of trousers, a ticket to the movies – in a typical market transaction, I choose and pay for my own desires.

Sometimes, however, I might buy something for someone else, and here trouble begins. If I am buying something – a goat, an HIV prevention course, a bit of paved road – for a complete stranger in a far-off land, the risks that something will go awry are far higher. How am I to know what is needed, where to send it, even whether it has been stolen en route?

This may be why we have aid agencies. Aid agencies are popular symbols of national generosity – witness the Tory commitment to ring-fence the Department for International Development’s budget, even as they speak of inevitable spending cuts elsewhere – and in principle should make better-informed decisions because they are in a position to put expert decision-makers on the ground.

In practice, things are not quite so simple. Aid agencies are government bureaucracies, of course. They are funded by governments and governments are also their typical beneficiaries. Even sympathetic critics tend to agree that aid agencies often spread themselves thinly across countries and sectors. Civil servants in poor countries are constantly tied up in meetings with aid agencies, while the agencies themselves fail to focus on what they do well.

SAVE US FROM OUR SAVIOURS

by Lindsey Hilsum

Good intentions are not enough. The chaotic mass of unregulated international aid is perpetuating suffering, argues Lindsey Hilsum.

It is the season to be generous. Aid agency appeals garner twice as much at Christmas and the New Year as at other times of the year. Heroic efforts by aid workers ease suffering: 'We alone established an air supply route and opened feeding centres . . . To sustain our single-handed effort, we need your support,' says Medecins sans Fronti. . .eres, raising money for war victims in Sierra Leone. Individual compassion plays its part. 'If you would like to send a message to a Bosnian mother, please enclose it with your donation,' says Feed the Children.

In the past decade, I have watched the emergency aid business " from the famines in Ethiopia and Mozambique in the mid-Eighties to genocide and the refugee exodus from Rwanda last year " grow from a small element in the larger package of 'development' into a giant, global, unregulated industry worth pounds 2,500 million a year. Most of that money is provided by governments, the European Union and the United Nations. Increasingly, they " like the general public " channel funds through non-governmental organisations (NGOs), which descend like migrating geese on every civil war and refugee crisis.

But the bland assurances of the advertisements " we are making things better, you can help " mask serious doubts about emergency aid. What would be called profits in any other sector have enabled NGOs to grow and proliferate. When a million refugees swarmed across the border between Rwanda and Zaire last year, more than 100 NGOs turned up. As a cholera epidemic swept through the chaotic camps, Operation Blessing " the aid wing of US evangelist Pat Robertson's right-wing campaign movement " brought in 70 doctors with no experience of Africa, working on two -week rotations. The German branch of CARE organised similar shifts. Officials of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees say they misprescribed drugs, took up space on cargo planes and got in professionals' way. Journalists, nearly as numerous as aid officials, watched eager workers scoop up orphans. The needs of lost, weeping children sitting next to their parents' corpses were undeniable, but some refugees abandoned their children believing the aid workers would do a better job of looking after them. They were wrong. Malnutrition and death rates in some children's centres were higher than in the camps in general.

The Rwandan capital, Kigali, became the aid capital of the world with 169 agencies resident, many staffed by young people on their first mission overseas. United Nations troops issued each newcomer with a handy laminated card featuring a map of the country and useful phrases in the local language: 'Hello.' 'Do not shoot.' 'My name is Bob.' 'Where is Kigali?' At one regiona l meeting I attended, 15 agency representatives, each carrying a two-way radio, turned up in white Toyota four-wheel drives. The Rwandan government official in charge of the region, whose job it was to coodinate the aid inflow, had no telephone, no car, not even a bicycle. He did not even chair the meeting; that was done by a woman from the UN.

There is a distinction to be made between professional agencies with experience in emergency relief and those who just want to be there or do something without knowing how. The International Federation of the Red Cross is pioneering a code of conduct as a form of voluntary regulation, but this may not be enough. 'To be a taxi driver in New York, you need a licence and an eye-check and some form of registration,' says Peter McDermott, head of Unicef's Emergency Unit. 'In these highly visible emergencies, we're increasingly seeing mom-and-pop organisations turning up who really have no qualifications whatsoever and are not being held accountable to certain standards.' But what about the established agencies? Should they be accountable to governments? To the public? Or to the refugees and victims of war they are supposed to help? The only form of accountability is through the press, but criticising aid agencies seems to be taboo. I, like other journalists, often travel to trouble-spots in aid agency planes or jeeps. It is nearly always the cheapest, and sometimes the only, way to get there. Perhaps that is one reason reporters rarely give aid workers tough interviews or write critical reports. Wars are frequently reported through humanitarian eyes " the dying child and the aid agency nurse is an easier story to tell than the complex causes of war.

One suggestion is for an international ombudsman, possibly under the UN, to review complaints about aid agencies. Standards could be enforced by UN agencies which coordinate disaster response, and agencies might only get official funding if they met certain qualifications. This, however, would not affect their ability to raise money from the public, and leaves unquestioned the ability and fitness of UN agencies to enforce standards.

These essentially technical measures do not address the central issue " that aid is not the answer to the problems of an increasingly violent world. Research conducted by Alex de Waal, an academic who founded the lobby group African Rights, shows that in the famines created by war in the Horn of Africa, food aid accounted for less than 15 per cent of what was consumed. 'No major famine of the past 10 to 15 years has had international relief as its major solution. The solutions are always political,' he says. Famine in Ethiopia and Mozambique only ended when war sopped. Studies by Mark Duffield of Birmingham University show that in Sudan, where war has continued for 12 years, famine relief has become integrated into the war economy, with soldiers, politicians and merchants rather than war victims as the prime beneficiaries.

War is the beast which eats the children. With food aid, we think we are feeding the children, but we may be feeding the beast. The International Committee of the Red Cross has a strict rule, under the Geneva Convention, of not providing food to combatants. But not all agencies follow the rule, particularly when passing through military checkpoints. A five-per-cent 'leakage' of food is generally regarded as inevitable, enough to feed several thousand militiamen or soldiers.

But aid is now the main plank of Western governments' policy in countries such as Sudan, Somalia, Afghanistan and Rwanda. Since the end of the Cold War, Western countries have disengaged from what used to be called the Third World. Last week's Observer Christmas special on peace was instructive " the four stories were of Ireland, Israel, the former Yugoslavia and South Africa, places of economic, strategic or historical significance where intense diplomacy is being followed by economic aid for reconstruction. The response of Western governments to the many conflicts in Africa and Asia, in contrast, has not been to try and end them by diplomatic, political, economic or military means, but simply to give aid. The received wisdom is that these wars are 'anarchic', rather than having complex, but explicable, environmental, historical and political causes. No one knows what to do, so the analysis proves that nothing can be done. Aid conceals the vacuum.

To Peter McDermott of Unicef, the only option for the aid agencies is to carry on with relief programmes while pushing politicians to re-engage in far-off wars. 'It's not an either/or. We don't have the luxury of standing on the sidelines and not addressing human suffering.' Yet it is not enough to behave like the UN official in Sudan who, after a meeting about what to do, exclaimed: 'Yes, we must think. We must analyse. But first we must act!' Thinking about the problem should not be permanently deferred. We seem to have accepted our governments' dictum that there is nothing we can do about conflict in countries where Cold War priorities no longer demand involvement. Every time starving children or refugees appear on the television, the public demands that 'something must be done'. Our first response should be to understand that sending aid is not 'doing something'. It is one aspect of a policy of doing nothing at all.

The Food-Aid Racket

Harper's Magazine

by Michael Maren

From a speech delivered in March by Michael Maren to the Camel Breeders, a group of Cornell University graduate students from various disciplines who are preparing to work in international development. Maren worked for the Peace Corps, Catholic Relief Services, and the United States Agency for International Development between 1977 and 1982. He is now a journalist in New York City and travels frequently to Africa.

As you prepare for and look forward to careers in international development, I am compelled to issue a warning. With the hindsight of someone who spent five years in the development business, I'm going to tell you that the development industry hurts people in the developing world. Its greatest success has been to provide good jobs for Westerners with graduate degrees from institutions like this one. I don't expect that any of you will take my advice and start looking for careers elsewhere. AndI'm in no position to criticize you for going ahead and working in development even after you hear me out. You see, I had a pretty wonderful career in the aid business. I can't remember ever having more fun. In fact, I was having so much fun that I didn't want to stop, even after I realized that our programs were hurting the very people they were supposed to help.