Film Blog

Newport Beach Film Festival

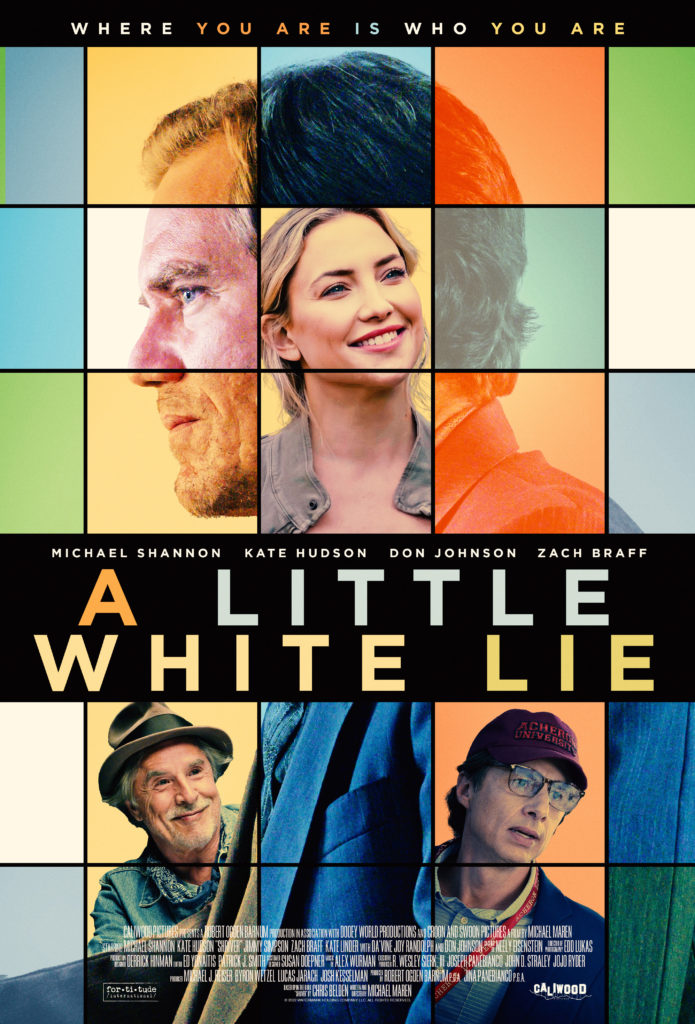

A Little White Lie will be screened at the Newport Beach Film Festival on October 14, 2022. Tickets are available here.

A Little White Lie will be screened at the Newport Beach Film Festival on October 14, 2022. Tickets are available here.

The title change from Shriver to A Little White Lie was a marketing decision, but as I've been reminded, the film is still the film. I hope you all get to see it.

Shriver Becomes “A Little White Lie”

A filmmaker doesn't always have complete control over what a distributor calls a film.

Here comes “Shriver”

Seven years in the making, filming interrupted 400 days by COVID, "Shriver" is finally edited and moving on to the next stages of postproduction: special effects, sound, music, color. Watch this space as we create a poster, trailer, and begin to bring this out into the world.

Kate Hudson and Michael Shannon in a PEOPLE exclusive first look at Shriver | Credit: Suzanne England

Kate Hudson and Michael Shannon are teaming up for a new comedy.

In a PEOPLE exclusive first look at Shriver, sparks fly between Hudson's and Shannon's characters in the film about a New York handyman, Shriver (Shannon), who is mistaken for a famous reclusive author with whom he shares a name.

Shriver accepts an invitation to attend a university writer's festival to deliver a keynote address where he meets Hudson's Simone Cleary, an English professor. Shriver plays a dicey game as feelings bubble between the two as he continues to pretend to be the author she believes him to be.

The comedy — written and directed by Michael Maren, and based on a novel of the same name by Chris Belden — also co-stars Don Johnson, Da'Vine Joy Randolph, Jimmi Simpson, Zach Braff and Aja Naomi King. It was produced by Jina Panebianco and producing partner Robert Ogden Barnum at CaliWood Pictures.

Hudson tells PEOPLE she was drawn to the project because of the starry cast.

"I'd been a fan of Michael Shannon's work for some time," Hudson shares with PEOPLE. "I was very excited to have the opportunity to work with him. Don Johnson is a legend and an old family friend, so I was very excited to be working with him. And having worked with Zach Braff in the past, I just knew I was going to be so much fun! I'm an avid reader, and at the core of this quirky, little film about writers is the story of the simple, human connections that we all seek."

"The COVID pandemic shut down production just one week before we wrapped, so waiting well over a year to reconnect with everyone and finally finish the film made this an experience that I will always remember," she adds.

The movie was a labor of love for the cast and crew and, in particular, for writer/director Maren, who was diagnosed with cancer in 2019 after casting Shannon, 46.

After overcoming cancer, Maren met Hudson, 42, who boarded the movie. The team spent three weeks filming in 2020 until COVID-19 halted production for 400 days.

Despite the hurdles, Maren tells PEOPLE his favorite part of making the movie was "to be able to work with this incredible cast" which he says "was a dream come true."

Having to halt production due to the pandemic "felt like a crushing blow," he adds.

"But a year later the spirit with which everyone came back together to complete this film was nothing short of inspiring," he says. "Watching Mike and Kate bring their characters to life while creating some really powerful on-screen chemistry is any director's dream."

As for what resonated with him about the movie, Maren says, "I think imposter syndrome is something that most of us feel at some point in our lives. It felt like a fresh subject for dramatic and comedic exploration."

Shriver is based on the 2013 novel of the same name by Chris Belden.

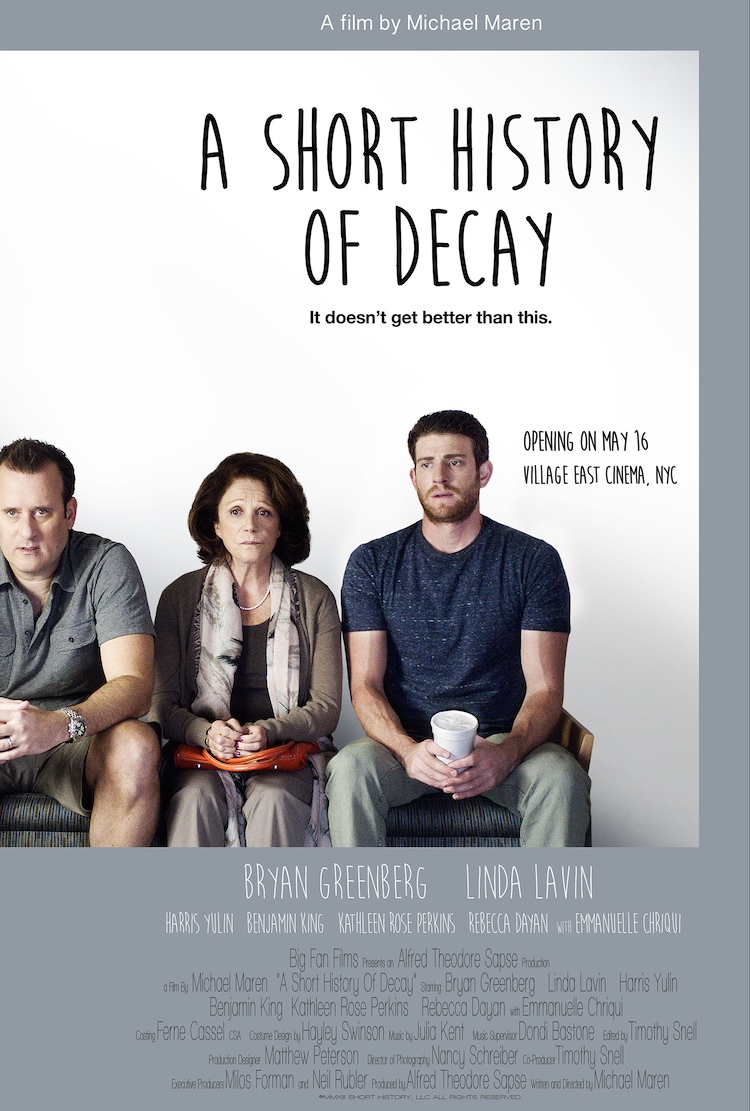

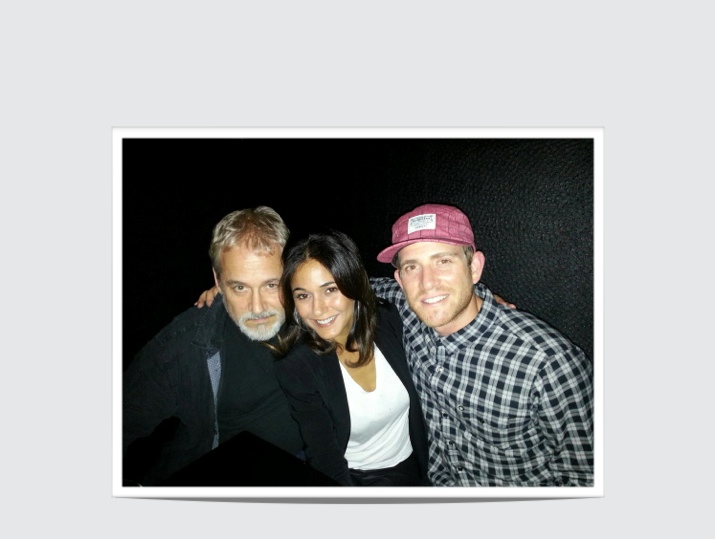

Media Week for A Short History of Decay

Things continue to happen for us at A Short History of Decay. The image above is from a live interview with me, Bryan Greenberg and Linda Lavin at the Apple Store in Soho. The interviewer is critic David Edelstein from New York Magazine. He seemed to like the movie. A lot. The discussion will be available as a podcast shortly.

We've also had a ton of other media this week.

• Here’s Bryan Greenberg on The Today Show.

• And on BIG MORNING BUZZ on VH1.

• Here's Part 2 of that interview.

• Bryan and I were interviewed on Huffington Post Live.

• And then Bryan, Harris Yulin and I spoke with Leonard Lopate on WNYC. • On Friday May 9, tomorrow, Linda Lavin will be on Hoda & Kathy Lee on during the 10 o'clock hour of the Today Show.

And there's been a lot more. This is extraordinary for a small film going into limited release, and it's happening because people are really responding to it.

Just a reminder, you can PURCHASE TICKETS for any of the shows next week in New York. Please come to one of the shows or pass this along to friends in New York.

Also, please sign up for our newsletter. We won't bother you too much.

Theatrical Release

I started keeping this occasional blog back when all I had was a few ideas on paper. It's been a long, strange journey. And now we begin another phase as A Short History of Decay opens on May 16 at the Village East Cinema in New York City.

We'd love for all of you to be there opening weekend.

And Now, Coming to a Theater Near You (perhaps)

We're thrilled to announce the release of A Short History of Decay by Paladin. The announcement received coverage today in Variety, Deadline Hollywood and Indiewire.

Here's the full press release:

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE, PLEASE

Contact: Shannon Treusch (917/225-7093) / Betsy Rudnick (646/713-4367)at Falco Ink.PALADIN TO MAKE 'HISTORY'

Michael Maren’s Directing Debut “A Short History of Decay” to

Open in Spring, 2014NEW YORK, NY – JANUARY 17, 2014 -- A SHORT HISTORY OF DECAY, starring Bryan Greenberg, Linda Lavin, and Harris Yulin will be released this spring by Paladin, it was announced by the company's president, Mark Urman. The film, which had its premiere at the Hamptons International Film Festival last fall, has been charming audiences on the festival circuit throughout the winter, with a theatrical opening planned for April. Noted author (“The Road To Hell”), war correspondent, and journalist, Michael Maren, makes his feature directing debut with the film, which also stars Kathleen Rose Perkins, Benjamin King and Emmanuelle Chriqui.

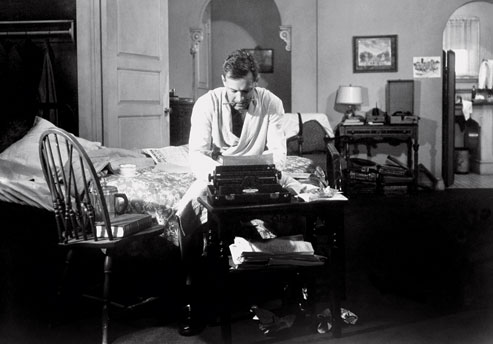

SHORT HISTORY tells the story of Nathan Fisher, a thirty-something Brooklyn “hipster” (Greenberg) whose writing career is stalled, much to the chagrin of his ambitious live-in girlfriend, Erika (Chriqui). When she unceremoniously dumps him, Nathan retreats into a depressive funk, not knowing where to turn-- finish the novel? work on the play?-- when he gets a call from his brother in Florida telling him his father has been hospitalized. Racing down to "snowbird" central, Nathan finds his father (Yulin) on the mend (albeit grumpy), and his normally addled mother (Lavin) a bit hazier than usual. His quick visit turns into an extended stay during which he discovers that his aging parents are actually in much better control of their lives than he is. He also meets a woman (Perkins)--his mother's manicurist, no less-- who is the polar opposite of Erika, but who may just be exactly what Nathan needs.

About the deal Maren says “we’re thrilled to have Mark and Paladin behind this release. His enthusiasm for the film and understanding of the effect it has on audiences, as well as his experience in the business, told me that he was the man to shepherd it into the world.”

Urman says, "whether you call it a serious comedy or a funny drama, A SHORT HISTORY OF DECAY makes for marvelous entertainment. Bryan Greenberg is completely winning as a rudderless man who needs to figure out who he wants to be ‘when he grows up,’ and he is surrounded by a terrific trio of actresses portraying the women who help him get there, particularly Linda Lavin, who is alternately hilarious and heartbreaking as someone whose love shines through even though her lights are dimming, and who still seems to have the right answers when it really counts."

Tony award-winner Lavin, currently co-starring in the NBC series “Sean Saves The World,” will be returning to the New York stage this May in Nicky Silver’s eagerly anticipated new comedy, “Too Much Sun,” having received her fifth Tony Nomination for Silver’s “The Lyons” last year. Perkins, portrays the ditzy network executive, Carol, on Showtime’s hit series, “Episodes,” the third season of which premiered this week, and Chriqui will be recreating her role as Hollywood princess Sloan in the forthcoming feature film of the long-running HBO series, “Entourage.” Greenberg numbers among his feature credits “Friends With Benefits,” “Bride Wars, and“ Prime,” and is also well known for his starring stints on the television shows “One Tree Hill,” “October Road,’ and, most recently. HBO’s “How to Make It In America.” Veteran character actor Yulin was most recently seen in last year’s acclaimed film, “The Place Beyond The Pines.”

The deal was negotiated by Urman and veteran entertainment attorney Alfred Sapse who also produced the film. Deals have also been entered into by Sapse and Bobby Gerber of ARC Entertainment for all post-theatrical domestic rights.

We’re Ready for Primetime

Okay, I'm a crappy blogger. For the past year (I don't even want to know how long it's been) all of my energies have been focused on making this movie. And now we're done.

We premiere at The Hamptons International Film Festival on October 12. Come on out and see us, and send your friends. Check out our website and watch the trailer.

A Short History of Decay from Michael Maren on Vimeo.

Writers Acting Like Writers

Every table in the coffee shop is occupied by young people furiously pecking away on laptop computers. Nathan scans across the room and from his POV each of them seems to possess the talent and self-assuredness of young of a young Beckett, Joyce, or Hemingway. He walks through, staring at computer screens.

This was was a scene description from an early draft of A Short History of Decay. In the story, Nathan’s girlfriend has just pointed out to him that he’s only pretending to be a writer, not doing the hard work, and she’s sick of it. Nathan heads off to a coffee shop to get down to business to prove her wrong.

The scene is meant to be part fantasy, a glimpse inside of Nathan’s fears. When he attempts to write he feels that all the places at the tables are taken and everyone is doing it better than he is.

The original idea was to fill the set with extras and coach them to to behave like writers, absorbed in their own work, soaking up the vibration of human activity in the cafe, and then to have them peer at Nathan as if to say, “you don’t belong here. You are not one of us.”

For months I thought about how to shoot this scene. What would I tell the extras? How would I get them to behave like real writers, not movie versions of writers. And then, well, I remembered that most of my friends are writers and could just “act naturally”

We shot the coffee house scene on the final day of photography on a beautiful fall day in Brooklyn. Almost everyone I asked showed up at 6 AM. The coffee was ready. We had some company: New York Magazine and The New York Times covered the shoot, which became something of an event.

The footage is beautiful, the performances natural and, from Nathan’s point of view, intimidating. And it was a perfect way to wrap my directorial debut. And, mostly it was fun. This filmmaking business is hard work. The potential financial rewards of making an independent film are highly uncertain. The doing is the reward, and so I tried every step of the way to make the doing rewarding. Every day was, particularly this one.

Photos by Heidi Gutman

A Short History of Production

On my list of priorities over the past few months, blogging has been pretty far down there. Since my last update we've gone through a month of pre-production, a month of production with a crew of around 50, and now we've entered a post-production phase.

We started shooting downtown Wilmington, doing our best to make little edited slices of it look like New York City. Then we moved to a "Brooklyn Apartment," a house in Wilmington that our art department turned into a brownstone walk-up. Bryan Greenberg and Emmanuelle Chriqui were in those scenes and I knew immediately that we had something special going on. Their incredible chemistry made the scenes sing, and it gave me the confidence I needed to really start working with the actors as they showed up on set.

The director with Emmanuelle Chriqui and Bryan Greenberg

On day three, Linda Lavin joined in quickly followed by Kathleen Rose Perkins, Rebecca Dayan, Benjamin King (a comic treasure, if you ask me) and Harris Yulin. The pleasure for me on the set every day was watching what these actors did with the words on the page and with each other.

The actors and crew worked very long days to get this done on time and on budget. There were days we reported on set at 5:00 AM and didn't leave until late at night. The Wilmington-based crew maintained an incredibly upbeat attitude throughout. Any thoughts of blogging about the shoot disappeared when I collapsed at night.

Wilmington is now wrapped, and editing has begun. This weekend we're shooting a few final scenes in New York, including one scene in Brooklyn Monday morning that I've been looking forward to since I first wrote it in the script. More on that later, as well as some pictures from the NYC shoot.

Coming Soon

Within the next week or two, I will be sharing the entire cast of A Short History of Decay. I couldn't be happier with the direction this project is taking. The production team is hard at work in Wilmington, N.C., where we will begin shooting on October 1. I can say with confidence that we are a GO film. I just want to say thank you to every single person who has supported me on this journey.

Two Steps Forward, and…

Since the purpose of this blog has been to tell the truth about all the ups and downs of the filmmaking process – and while lately all the news has been good, which is a whole lot more fun to write about – I need to tell you about the last few weeks, which have confirmed a few of the most basic filmmaking credos for me, one of which is that you don’t have a green light until the ink is dry on the check, and the check has cleared the bank.

A few weeks ago, we were in pre-production on ASHOD. The film was fully cast, and seemed to be fully funded. We opened production offices in Sarasota, Florida, and the A.D. and UPM and D.P. had all convened there. We were putting in long days and chowing down on stone crabs at Walt's Fish Market in Sarasota. We had reduced the budget of the film to the barest bones, and I had been shaving pages off the script in order to make this lean and mean shoot happen – even it if meant losing some scenes and moments that were important to me.

And then the other shoe dropped. A major investor who had committed, well… simply changed his mind. Why this happened is anyone’s guess. This investor wasn’t someone I had direct dealings with. A guy in LA was talking to a guy in New Orleans who was talking to this guy in Palm Beach. It was like an elaborate game of phone tag but with a lot of dollars attached. And then… silence. Phone calls not returned. And slowly, a pit in my stomach which grew and grew until it was confirmed.

We are going to have to postpone production. Re-group. Re-think. Find a new investor, or new series of investors. My wife turned to me (we were in a car on our way back from a funeral when this news hit us) and said “this is going to have a silver lining. You are going to look back at this, six months from now, and be glad it happened this way.”

Now, my wife is no Pollyanna. And deep down I feel the same way. We were shaving too much off the budget. Making compromises that felt nerve-wracking, all in the service of just getting the movie made on schedule. Now, my producing partner and I have increased the budget. We’re going after different investors with a different strategy. Everyone – from the cast to the crew – who has believed in this project from the beginning is still on board. All the original investors are hanging in there. They were doing this for love, and they still are. We’re going to make ASHOD, and we’re going to make it the way it needs to be made. This is the story of getting an indie film off the ground, and up until now, I am aware, I had a crazy-good run. It felt almost too good to be true. And guess what: it was. So this is the next stage of the game, and the thing that separates filmmakers who actually get their movies in the can from those who give up.

In my previous career, I was a war correspondent. This is a war – the war of art, the war of building a skyscraper from the top down, the war of combating exhaustion, disappointment and insecurity and moving forward, day by day, to the moment – we are hoping it will be this fall – when I will be saying those two, most precious words:

And…action!

Grace, Magic, and Power

I took a moment yesterday, amongst the barrage of phone calls and emails, to consider how far my film project has come. It was born out of frustration and intense creative desire and a need to change the whole way I thought of my work and my career. I’ve done it my way, on my own, after a lot of years of thinking (or being told) that I couldn’t, or shouldn’t. That I was thinking too big, or coming up with ideas that were too out there; that no one was making grown-up movies. Or that no one would take a chance on a first-time director. Well, of all the many mind-blowing things that have happened over these past few months, maybe the most amazing is this sense of what is possible. Goethe once wrote this: “Whatever you dream you can do, or believe you can do, begin it. Boldness has grace, magic and power in it.”

Tomorrow I’m heading back to LA with my producing partner for a few jam-packed days of meetings with actors, our casting director, agents, a cinematographer, and investors. Several of the key roles in “A Short History of Decay” have been cast with some staggeringly wonderful, remarkable, gifted and well-known actors. I’m not being coy here – I’m just not comfortable naming names yet. Call me superstitious. But suffice it to say that I am beyond gratified with the response to the script, and with the support I’ve received from people in the industry. I’ve come to see that casting a movie like this is like putting together a giant puzzle. Or, as my wife has recently described it, like building a skyscraper from the top down. We have most of the pieces in place, and still a few more key ones to go.

After my LA trip I’m meeting my producer/first assistant director Buffalo Mike Hausman in Florida where we’ll cover a lot of ground – from Jacksonville to Sarasota – location scouting and meeting with crews. ASHOD has a start date. Mind-blowing but true. We’re set to begin shooting this thing in early June.

The Importance of Showing up

For the past last two months everything has moved steadily in the direction I’d hoped it would — which is why you haven't heard from me in a while. This is what’s happened:

First, Mike Hausman finished my budget. The initial draft of the budget totaled about $4 million. That was too high. Mike and I both felt that in order to secure investors’ backing of a film with a first-time director, we’d have to get it down below $3 million. And since we’re planning on shooting in Florida, it means that we “only” need to raise about $2 million in private equity. That’s because Florida offers a tax credit of between 20 and 30 percent, depending on a series of variables.

In order to work the budget down, we had to reduce the number of shooting days. Don’t ask me exactly how that was done, but Mike went back to the drawing board and produced a budget for $2.8 million based on 25 shooting days. That puts a lot of pressure on the production, but with Mike working as 1st assistant director, we’re confident that’s doable.

But now, the hard part. Where to get the $2 million? On one level, the answer is simple, you ask for it. Several people have suggested the crowdsourcing model, but this is simply too much money to raise in that manner. And although this script bears all the classic hallmarks of an indie picture, I want to make a film that will be a commercial success, or at least make earn more money than it cost to produce. I wanted to be able to go to people and offer this as an investment. Crowdsourcing even a portion of the budget seemed to me a signal that this was not a viable commercial venture.

I know what I’m good at and what I need help with. I needed a producing partner who could explain the investment, the risks, the potential rewards, and could also talk film. Someone who could speak with authority about the script, the process, and the business.

I met him at a dinner party that I almost skipped. (I also met my wife at a party I almost skipped.) My wife was out of town, and my son was insistent that we stay home and watch The Hangover again. He pouted and complained for the entire 15-minute ride to the party. As Woody Allen famously said, “Eighty percent of success is showing up.” That has indeed been my experience.

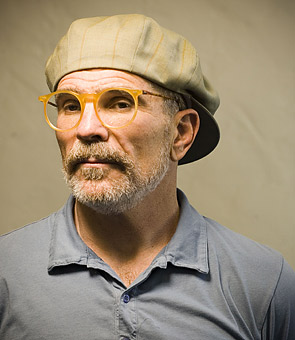

I’ve known from the beginning that in order to get this done, I’d have to talk to everyone I met and tell them what I’m up to. (Which isn’t difficult because everyone eventually asks, “So what are you up to?”) The hosts of the party introduced me to Alfred Sapse, who I’d known by reputation as an entertainment attorney. Alfred moved to Connecticut from Malibu looking for a lower key place to raise his kids. He’d been working for his old clients and quietly producing low budget films.

We hit it off immediately. The next day I sent him a copy of A Short History of Decay. Two days later we were partners. Last week we met in New York with Mike H, to move the process forward. And since Albert came aboard, things have been moving very quickly.

A corporation has been formed: Short History, LLC.

Our first investor is now aboard, a very smart investor whose presence we hope will convince others give us a serious look.

There’s more than that to tell, but I’ll do it in the next post, casting for talent.

Click HERE to see the first post in this series.

Notes to a First-Time Director

When I was on the set of Phil Spector a last month I got some great advice on directing my first film, A Short History of Decay, from David Mamet. A week later, as I was heading to LA, it occurred to me that many of my friends in the business would also have some interesting things to say about taking that first daunting step into directing.

How does a neophyte walk into a situation crowded with experienced professionals and start running the show? (Or, does one even attempt this?) How does someone who hasn't acted since stinking up a high school production of Othello talk to seasoned actors about their craft? So, camera in hand, I started asking them. As Mamet had predicted, everyone was generous, supportive and helpful.

Techies P.S.: This was recorded with a Nikon D7000. Okay, some of these are a bit out of focus. When I realized that I couldn't really see through the camera's LED screen, I bought a Zacuto viewfinder which allowed me to actually see what I was shooting. I recommend the product to anyone shooting with an HDSLR.

What I Learned Staring at the Back of Al Pacino’s Head

We were on our way to grab a quick bite, waiting for the elevator in a Brooklyn courthouse. David Mamet looked at me and said: “The best thing about directing your first film is how supportive everyone on the set will be. Everyone will be rooting for you to succeed.” Then he added, “Let me know if there’s anything I can do.”

For me, moving toward directing my first film, this was welcome encouragement from a great director, a director whom I’ve long admired. Whose book On Directing Film, I’ve devoured.

But the more interesting story is how I ended up chatting with David Mamet in the first place. And it’s a story that starts, as does the story of my making this film, with a decision to follow my own instincts against all advice and conventional wisdom about how to make a movie.

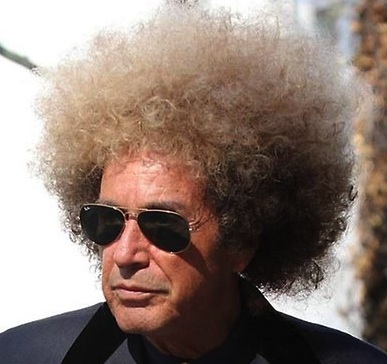

This part of the story begins with Milos Forman. Milos was among a small circle of trusted friends to whom I’d given early drafts of A Short History of Decay. I was looking for any notes he might have as well as any tips he might offer on directing. Mostly, I was looking for the reaction of a veteran multiple Oscar-winning director to my casual remark that I was planning on directing my own script. “I only have one piece of advice,” Milos said in his deep Czech accent. “Don’t listen to anybody. You’ll know what to do.”

I’ve followed that advice ever since.

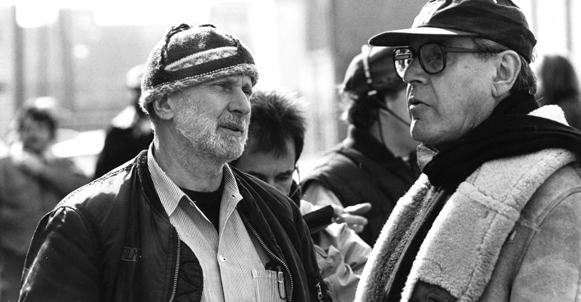

Milos loved the script enough to pass it along to Mike Hausman. Mike is an amazing producer who often doubles as first A.D. (assistant director). He’s produced films such as Amadeus and Brokeback Mountain, to name only two. He’s also produced most of David Mamet’s films. The first A.D. runs the set. I need someone who can do that.

I’ve previously written about my initial meeting with “Buffalo” Mike Hausman. So you can read it here.

Mike is now producing and acting as first A.D. on a film for HBO, the as yet untitled Phil Spector biopic which stars Al Pacino and Helen Mirren. Mamet wrote the film and is directing. I told Mike that I’d like to spend some time on the set, to watch him work and see how he runs the show. His answer was to invite me to be an extra. I would play a journalist in the courtroom. “Great,” I told him. “Because I still consider myself to be a journalist.”

“I know,” he said. “That’s what I’m afraid of. You’ll probably overact.”

So, continually reminding myself not to overact, I arrived at “holding” for extras, which was set up in church in Brooklyn Heights. I joined dozens of other extras— or background artists — most of whom seemed to know each other from previous TV and film jobs. They would be spectators, security guards, jurors, journalists and other other bits of what some referred to as “moving wallpaper.”

The scene recalled for me the feeling of being a journalist and landing in a new country for the first time. I watched, learned, and immersed myself in a fully realized subculture with its own language and customs. And since most of the work of being an extra background artist involves sitting around, I got to know a few people. It was a blast.

I spent three days staring at the back of Al Pacino’s head as he wore some crazy Phil Spector wigs. I watched Mike Hausman run the set, which all of the extras agreed was one of the most relaxed and friendly they’ve ever been on. And I got to meet some of the amazing people who work for him, some of whom I will work with on my film.

And I got to sit for hours and watch an extraordinary and accomplished director create his vision.

(My star turn was when one of the cameramen asked me to slide a bit to my left. Then a bit more. I asked him if he was trying to get me into the shot. "No," he said. "I'm trying to get you out of the shot. You're ruining Al's closeup.)

And as I sat there day after day, I thought to myself, This is good. This is what comes from giving yourself permission to do what you want to do. From taking Milos Forman’s advice: “Don’t listen to anybody.”

Or I suppose I should add to that, don't listen to anyone who tells you what you can't do.

The Wages of Fear

First, a brief update on A Short History of Decay. I’m awaiting the budget and breakdown from my producer. It’s a hugely complicated process that results in a document that is very often longer than the screenplay itself. During this time I’m talking with potential investors. I can’t talk any particulars until I have the document, so we wait. And I turn back to several television projects that are on my board.

I keep a bulletin board in my office with the titles of various projects I’m working on, or want to be working on; It’s easy to lose track. The board also reminds me of why I’m making a film on my own. Every project on it has a back story that includes a litany of reasons why it can’t be made.

If you want to make a living as a screenwriter or television writer there are certain things you must understand: You can’t sell a television show with a female ensemble cast. Baseball movies don’t make money. Period pieces are too expensive to produce. You can’t show a sick child in the opening act. You can’t set the drama outside the United States. You can’t have more than one foreign character in your movie or TV show. The lead has to be an American. A television show has to be a procedural; you must resolve at least one storyline in each episode. And by all means do not write a baseball movie with an all Cuban, female cast set in the 1930s.

What you should do is figure out what was successful ten minutes ago, tweak it a bit and hit the streets with your script before the buzz dies about the thing you just ripped off.

I exaggerate, but not much. This is a symptom of the climate of fear that has always gripped the entertainment industry but which has of late reached apocalyptic proportions. Agents don’t want to go out with offbeat material, and junior executives don’t want to pass it along to the higher-ups. If you’re working on something and you hear that someone else has beaten you to the punch with something very similar, write faster and wish them well. If their project crashes and burns, yours will never see the light of day.

A number of years ago my wife and I developed a medical procedural set in the world of fertility clinics. We were partnered with big TV star fresh off of a mega-hit series who had a development deal with Warner Brothers. All good. Except... we’re all buoyed about by the same zeitgeist. If you’ve got an idea, and it feels good or commercial (or both!) then you can pretty much assume that half a dozen other writers were struck with the same epiphany in the shower this morning and are busy drafting emails to their agents.

That was the case with our fertility drama. We learned, while sitting in a conference room at CBS, that there was another project that they were also considering that had been brought to them a few weeks earlier by a team of emmy-winning writers. They went with the other project.

Several months later we turned on the TV and watched the show with something approaching paralyzing trepidation. It was -- pun alert! -- as different from the show we’d conceived of as possible. And it was godawful. Just terrible. And it didn’t last much beyond the pilot, from which I derived some smug satisfaction until I realized that it meant that nobody was even going to look at a show in the fertility “arena” for at least a decade. And that was the end of that.

Nobody wants to hear that a show or a film didn’t do well because it wasn’t well done. That’s too hard to quantify, so everything is reduced to a formula based on facile and false equivalencies. There’s little room for aesthetic judgement in the economy of fear.

A television pilot I recently wrote about doctors in a war zone (American doctors) was quickly conflated with a chirpy feel-good medical drama set in a tropical paradise from people who made Grey’s Anatomy. The only thing the shows had in common was doctors and Third World. I’ve actually spent years living in refugee camps in war zones. I was creating real characters and drama based on that experience. There was no confusing it with escapist entertainment -- not that there’s anything wrong with that.

People who liked my pilot were waiting to see how the other one did. It didn’t do well.

The lesson that producers took from that was you can’t take doctors out of the country.

But then there’s Slum Dog Millionaire. And there’s Mad Men and Six Feet Under and other films and shows that broke lots of rules, maintained their integrity and did phenomenally well. And when you hear what it took to get these things made and distributed you can only gasp in admiration of the persistence and singularity of vision that it took to fight through the resistance. Ultimately it’s powered by respect for the audience and by the belief that what’s good is good whether your hero is an all-American masked avenger or a Mexican sharecropper. It’s hard to keep believing that when you’re constantly fed that list of things you can’t do. Until finally you just decide to do it anyway, which is why I am where I am, starting to raise money to make my own film.

It’s Come to This

I’ve been a working screenwriter for more than ten years. (I was a journalist before that - see the other pages on this website.) I sold the first three or four scripts I ever wrote and thought “this is easy.” I used to get hired to write movies that I pitched to studios. And sometimes I got hired to write films that they needed a screenwriter for. I wrote a spec script based on John Hockenberry’s memoir, Moving Violations. Everyone loved the script, but no one wanted to make a movie about a guy in a wheelchair. (Can’t you hear the studio execs: “I love it, but can you lose the wheelchair?) That script got me work, but it never got made.

I worked on some indie projects (most notably the cursed Janis Joplin biopic) and other things that collapsed or disappeared for reasons largely beyond my control. I say ‘largely’ because I’ve made some mistakes in judgement. I’ve sat and waited for the phone to ring when I should have been banging on doors and selling myself and my ideas. And I’ve wasted too much time pursuing projects that weren’t good ideas to begin with.

I had an epiphany a few years ago when I was pitching a film over at Fox Searchlight. The exec said to me and the producer I was partnered with, “This is great. Bring me a script, some talent and a director and we’ll seriously consider it.” And I thought, if I have a script, some talent and a director, what the fuck do I need you for?

I probably should have embarked on an immediate career course correction at that point, but I didn’t. It was some combination of fear and inertia that kept me pitching ideas to producers, rather than producing my own ideas. For example, several years ago, because people liked Moving Violations as a biopic, I was asked to pitch my take on the life of J. Edgar Hoover to Brian Grazer's company. (One of many biopics that came my way.) I spent a month reading everything I could on Hoover, prepared a pitch and then presented it to some development people at his company. I never heard from them again. They ended up hiring Dustin Lance Black, who won an Oscar for Milk. I don't blame them; I blame myself for trying to get a piece of someone else's dream project instead of chasing after my own dream project.

It took the writers strike, the collapse of the economy, and a boatload of frustration before I developed the resolve to follow my instincts and arrive at this: The only way to move forward is to write, produce and direct a film myself. That was last December.

As 2011 dawned I set out to write a film that could be shot on a micro-budget. I was thinking somewhere in the vicinity of a million dollars, or less. A film that didn’t require car crashes or explosions. A self-contained story that would utilize interiors. A story that mattered to me.

It took me about six weeks to complete the script.

And here we are. I’m hell bent on producing and directing this film now. I've decided that I’m going to live-blog (so to speak) the process of making a film from scratch. It’s risky, because:

a) I’ve never done anything like this before.

b) I’m most likely going to fail and embarrass myself.

c) I could be committing myself to 10 years of blogging this project.

I’m going write about things as they happen. (Some things have already happened, but I’ll get into that in the next post.) I’m not going to name names...at least for now. I don’t want to write about the people I’m talking to unless they give me permission to do it.

I've already gone to a number of friends and and asked for favors, for notes on the script and for introductions to people they know who might be able to help me. That all sounds perfectly simple, I know. But I've never been good at asking people for favors. Or, another way to put it is that I've never been particularly entrepreneurial precisely because I saw it as asking for favors. I'm being proactive, even aggressive, even though it's not my style. I don't have to be comfortable doing it. I just have to do it.

The first draft of the script was entitled: A Short History of Decay. I took the title from a book of philosophy by E. M. Cioran that I love. I thought it sounded intellectual and indie-smart. The book’s subject is indeed apropos of the underlying theme of the film. (It’s a comedy, though a darkish one.) I also thought it was a signal from the start that this wasn’t going to be light summer fare.

A director friend in LA told me to change the title. No one is ever going to want to even read a script with that title. My wife told me she thought it sounded pretentious.

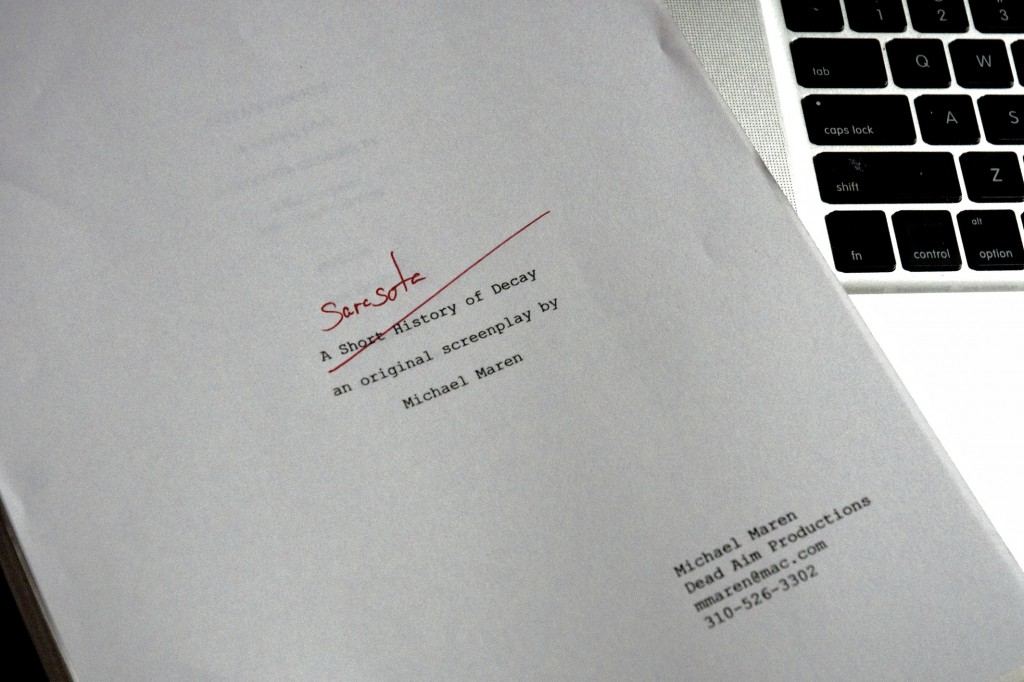

The title of the script is now: Sarasota.

Go to Part 2.

Flavor of the Month

Several years ago I was in LA to pitch a project with a young, hot director. He was fresh off a big indie success; i.e, lots of festival praise and award nominations. The first night we were in town, his agency threw a reception for him at the flavor-of-the month restaurant on Melrose. It seemed like half of Hollywood showed up. We arrived at the party together, and I soon found myself deep in conversation with some managers from one of the big management agencies. I should have known something was wrong from the beginning when they were so warm and solicitous toward me. When the conversation evolved into “are yo u free for lunch?” I dutifully informed them that I was not the director, just the screenwriter that he was working with.

u free for lunch?” I dutifully informed them that I was not the director, just the screenwriter that he was working with.

Normal human beings might have been embarrassed at that moment, but the reaction I got from them was profound irritation. They had wasted 10 minutes of their precious time and energy being polite to a nobody. They both turned and walked away from me as fast as they could without even a ‘nice talking with you.’

I suppose I would have felt worse about that if it hadn’t been so comically absurd. I spent the rest of the evening watching people surround the director. Lawyers were there to try and poach him, managers were trying to sign him. Everyone was trying to make an impression. I was a little envious — who wouldn’t want to be the recipient of such a full-on ass-kissing? — but at least I was drinking for free.

Over the next few days we had meetings in some very impressive rooms. His presence assured that the top development execs at the studios heard our pitch. We had lunch with Jim Carey. Two studios ‘bought’ the pitch in the room. Life was good. For a very short time. (You knew this wasn’t going to end well.)

A few weeks later the director informed me that he would only do the project if he could write the script himself. I was at first puzzled, and then angry. It was my project. I’d held the option on it for few years and had worked hard to keep it all afloat. Granted, it was the heat under his career that had garnered all the attention the project was getting at the moment. He must have felt that he was holding all the cards. But I passed. I was going to keep control of my own project, my own script. That was then end of that.

The director already had another project in the works; an adaptation that he had done himself. Of course, I followed his career and went to see the film when it was released. The film was, by any objective standards, awful. Despite an incredible cast, every scene fell flat. Admittedly I was not in the mood to give his movie any benefits of any doubt, but there was no getting away from how embarrassingly bad was. (Okay, I’ll stop.)

I’m not the only one who hated the movie, because he hasn’t been heard from since. I’m sure that his agency isn’t throwing him any big parties, and the managers who were looking to sign him probably don’t recall who he is anymore. I’m lucky to have unhitched my wagon from his horse when I did.

Whatever people were whispering in his ear over that time, he must have believed it. It's hard not to. Who doesn't want to be told he's a genius? That's not to say you shouldn't enjoy the attention and the spotlight. Take it while you can, but don't make the mistake of believing it. Ultimately for writers, directors — for any artist — it's about the work. We can't take our cues about who we are from what others tell us about that work, good or bad.

I’m a Big Fan

The first evening after the first time I ever went on a series a Hollywood pitch meetings, I was walking on air. I was with my wife, and we’d sat down with producers at Paramount, Fox as well as a number of successful independent producers in Beverly Hills. Everyone loved the project, a love-story murder mystery, very very loosely based on one of my wife’s books. With each meeting, the level of enthusiasm seemed to rise. This is brilliant. This is exactly what we want. I have no questions about this. This is perfect for Gwyneth. That night in our hotel — the Chateau Marmont, of course — we were fantasizing about the auction that was certain to follow.

The phone never rang. No one even bothered to call back to pass on it.

Several months later I pitched it to Mike Medavoy. I sat on the couch in his office next to Reese Witherspoon, who had attached herself to the project. Medavoy sat through the entire pitch meeting looking like he’d rather be at the dentist. He was surrounded by assistants who picked apart my pitch and wondered who would ever watch such a film. Under a barrage of criticism I veered off course and stumbled inarticulately through the rest of the pitch. I phoned my wife after that meeting to tell her I'd totally blown it.

Several months later I pitched it to Mike Medavoy. I sat on the couch in his office next to Reese Witherspoon, who had attached herself to the project. Medavoy sat through the entire pitch meeting looking like he’d rather be at the dentist. He was surrounded by assistants who picked apart my pitch and wondered who would ever watch such a film. Under a barrage of criticism I veered off course and stumbled inarticulately through the rest of the pitch. I phoned my wife after that meeting to tell her I'd totally blown it.

The next day Medavoy bought the project.

I did learn some lessons from that, but it took years. In the immortal words of Dorothy Parker, “Hollywood is the only place where you can die from encouragement.”

Hollywood, despite the fact that they’ve managed to commodify irony on the screen, (The Big Picture, Mistress, Day of the Locust, Swimming with Sharks, et al,), doesn’t seem to recognize it when it's in the room. They know they’re doing it, but can’t help themselves. I used to be flattered whenever I was told that a particular executive, producer, director or whatever was a BIG FAN of my work. Now, when I hear the phrase big fan, I know it's meant as a compliment but what it really means is this: I'm screwed.

Several years ago I wrote a screen adaptation of John Hockenberry’s incredible memoir, Moving Violations. Everybody loved the script. I had meetings with directors and stars. I was told that the script had gotten me a lot of fans. But as I would sit and listen to people telling me how brilliant it was, I would be overcome with a sick, sinking feeling. The more praise they heaped on my work, the more I understood that I was being handed a consolation prize.

There is one phrase worse than, “I’m a big fan,” however. The real kiss of death is: “You’ve really done a lot of work on this.” Translation: “You’ve wasted a lot of time.”